WASHINGTON — An executive order signed by President Donald Trump aimed at denying birthright citizenship to the children of immigrants born in the United States is likely to face immediate legal challenges, but if If enacted, it could have dramatic consequences in places like South Florida.

The order states that the federal government will no longer be able to protect children born to parents who are in the United States illegally or whose parents’ presence in the United States is lawful but temporary (visa, employment, visa, etc.). (including those staying in the country) will not be granted automatic citizenship. tourist visa. The order only affects children born after Monday.

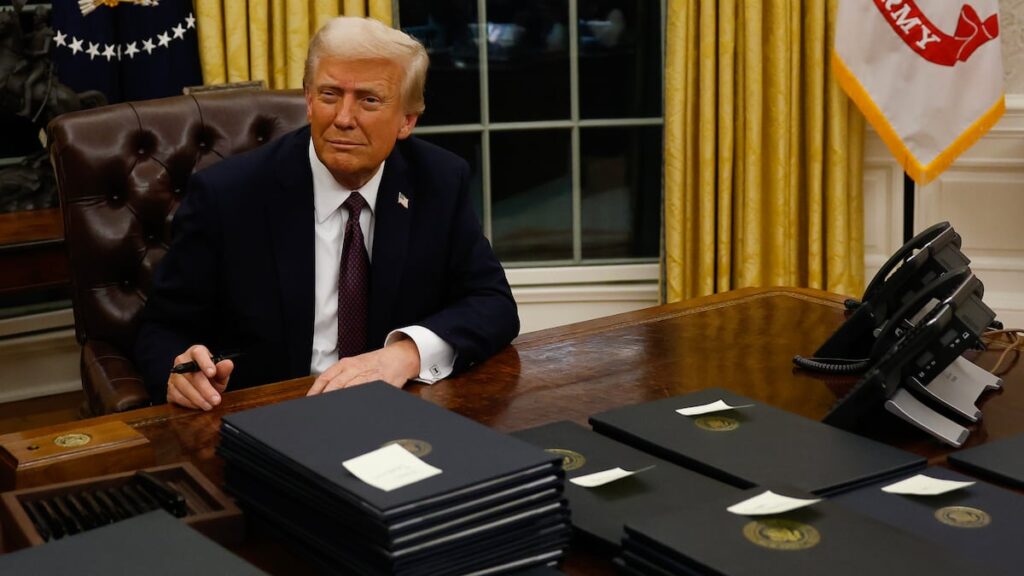

President Trump told reporters in the Oval Office on Monday night that he was aware the order could face legal challenges.

“We’ll see. We think there’s very good evidence,” the president said.

Birthright citizenship is protected by the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. But the Trump administration asserted in its executive order that the 160-year-old constitutional provision “has never been interpreted to universally extend citizenship rights to all persons born in the United States.” , this legal argument is almost certain to reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

Constitutional amendments may be proposed by Congress through a joint resolution passed by a two-thirds vote, or by a convention called by Congress on the application of two-thirds of the state legislatures.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis and Republican state lawmakers are awaiting President Trump’s executive orders on immigration, with plans to return to Tallahassee next week to potentially enact new policies to implement the new president’s policies. are.

As of Monday night, it remained unclear what Republican legislative leaders intend to enact to support federal immigration enforcement in Florida. In the past, the governor has pushed to require hospitals in the state to ask patients whether they were in the U.S. with legal permission to help the administration track patient numbers for future policy. asked the lawmakers.

Beyond tracking hospital data, it’s unclear what more the state can do to enforce denial of birthright citizenship in Florida.

But any action against birthright citizenship could have significant ramifications. Between 2010 and 2014, about 7 percent of children in the state, or about 280,000 children, had at least one family member, according to a study by the American Immigration Council, a think tank and immigration agency in Washington. He was also a U.S. citizen who was living in the country illegally. Advocacy group.

President Trump’s executive order does not seek to strip the birthright citizenship of immigrant children currently in Florida illegally. Rather, it only affects future births.

But potential legal hurdles remain.

The Fourteenth Amendment provides that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and of the state in which they reside.” This provision was ratified into the founding documents in 1868. Prior to the amendment, men and women of African descent could not become citizens.

In 1967, the Supreme Court raised concerns about birthright citizenship in a case concerning a federal law that stripped Americans who voted in foreign elections of their citizenship. In a 5-4 decision, the court said the Fourteenth Amendment is intended to “protect all citizens of this country from the coercive destruction of their civil rights by Congress.”

Justice Hugo L. Black wrote in Afroim in 1967 that “the very nature of our free government requires that one group of citizens temporarily holding public office can strip another group of citizens of their citizenship rights.” “It is completely contradictory to have a rule of law.” v. Rusk.