Florida is supposed to police the state’s biggest sources of water pollution: agriculture and development.

Instead, regulators and lawmakers have protected the major industries at nearly every turn, a Tampa Bay Times investigation has found.

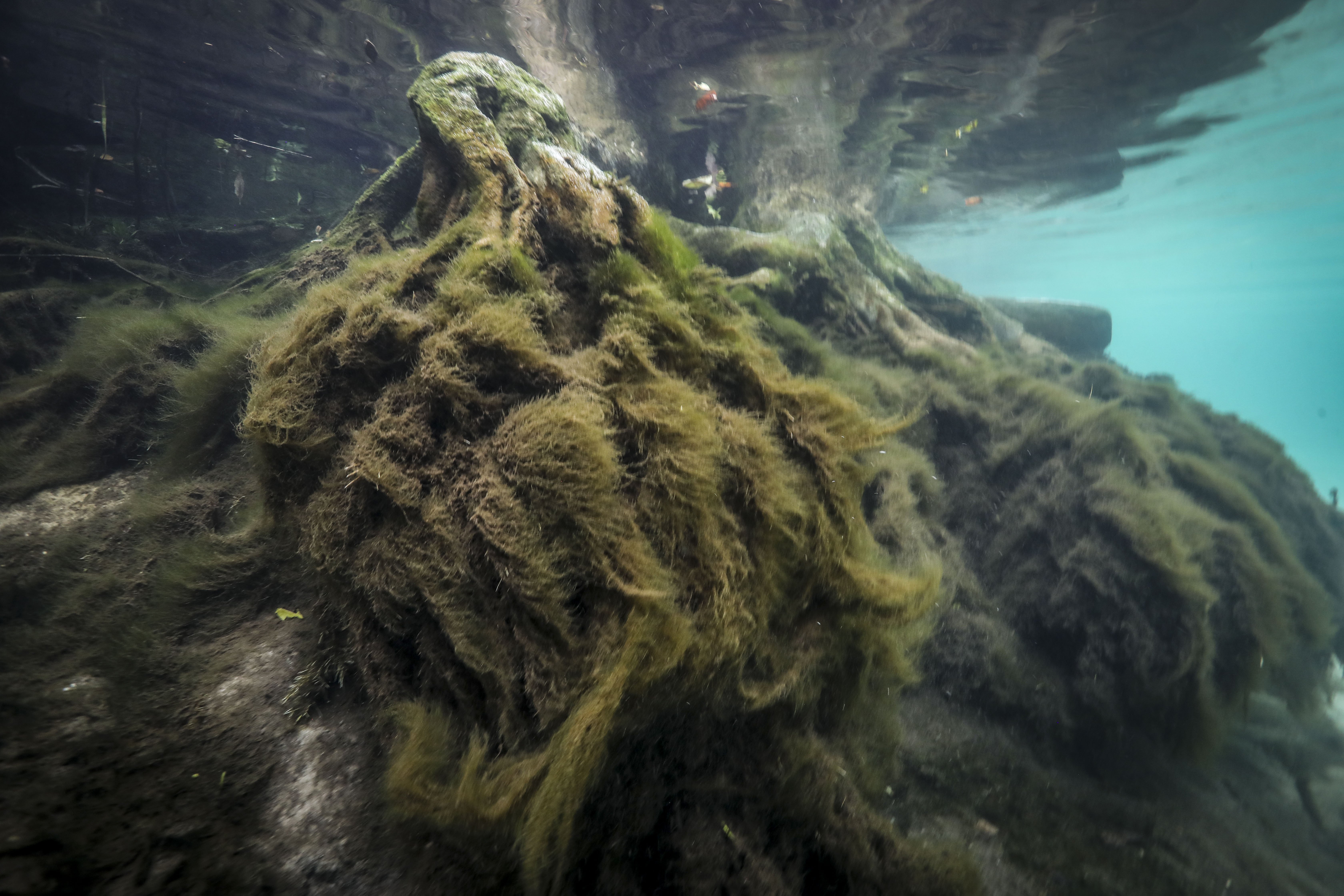

The approach has resulted in hundreds of waterways across Florida growing dirtier for decades — including the Caloosahatchee, where algae blooms have fueled fish kills, and the Indian River Lagoon, where scores of manatees starved to death as the ecosystem neared collapse.

“People know what it would take to clean our waterways — it’s not rocket science,” said former state Sen. Lee Constantine, an Altamonte Springs Republican who led conservation measures over nearly two decades in the Florida Legislature. “The problem has always been the political will to do it.”

Regulators don’t track runoff from individual polluters, leaving big companies unaccountable for tainting waters and keeping the public in the dark.

Florida officials ask developers, farmers and ranchers to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus contamination by using methods recommended by the state. In return, regulators assume that the companies aren’t harming the environment.

No one bothers to check, the Times found.

The state’s approach amounts to an honor system. In theory, it aims to balance environmental needs with the economy. But over and over, Florida leaders have sided with business at the expense of nature.

( DIRK SHADD | Times )

Take their handling of controls for urban runoff.

In 2007, regulators discovered the methods were a bust: Far more chemicals fouled the environment than officials originally believed.

Florida leaders didn’t fix the problem. They let matters get worse.

Over nearly two decades, the state allowed developers to build over a stunning amount of land.

A Times analysis found that builders transformed more than 550,000 acres into roadways, master-planned communities and shopping plazas — equivalent to developing an area the size of West Palm Beach every year.

Dramatic growth happened around some of the state’s most struggling waters, including beloved places like Biscayne Bay and the Hillsborough River.

Beyond dragging on better controls for urban runoff, state officials have largely ignored a mandate to ensure that pollution-reduction efforts farmers put into practice actually work. The state has continued to pour money into an unproven program despite dozens of waterways surrounded by agriculture showing rising contamination, the Times found.

Among them is Jackson Blue Spring, near peanut and cotton fields in the Panhandle. Farmers on most of the surrounding cropland say they use the state’s methods to limit contamination.

Yet nitrate levels in the spring routinely average more than 10 times the healthy limit, the Times found.

Improving water quality isn’t even the primary goal of some of the state’s methods. Florida regulators set recommended fertilizer limits that aren’t based on environmental health. They’re instead designed to help farmers growing oranges, sugarcane, tomatoes and other crops earn as much profit as possible.

“Farmers are basically given a free ride,” said Robert Palmer, a marine biologist and board member for the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute. “It’s not working.”

Under the federal Clean Water Act, states are responsible for curbing much of the runoff. But the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has taken a hands-off approach to enforcing those duties, while Florida has been slow to adhere to them.

The delays save money for multibillion-dollar industries that hold incredible sway in Tallahassee. Florida relies on farmers and developers to provide safe, affordable food and housing for millions of residents living in and moving to the Sunshine State.

Companies and industry trade groups also contribute generously to political causes, a Times analysis shows. They’ve spent more than $50 million on lobbying alone since the state started recording comprehensive data in 2007. Over the last three decades, they’ve given at least $200 million to candidates and committees.

Activists have repeatedly, and successfully, sued the government to spark action. One lawsuit forced regulators to study dirty waterways and establish cleanup goals. Today, that work stands as the bedrock of Florida’s restoration strategy.

The state has so brazenly bucked regulation, it once joined forces with lobbyists from polluting industries to stymie a federal effort to establish more protective standards. As part of its pushback, Florida cited several waterways as success stories, including the Indian River Lagoon.

A decade later, the Lagoon became a wasteland.

Seagrass vanished, leaving haunting underwater moonscapes. Without food, hundreds of manatees starved.

The Department of Environmental Protection declined to make agency leaders available for interviews. In a statement, Alexandra Kuchta, a spokesperson for the agency, said Florida has made significant progress in recent years by investing in legislation and policies focused on improving waterways.

“Water quality problems did not arise overnight, and solutions will take sustained long-term effort,” the statement said. “Through advanced data collection, scientific analysis and evaluation of the health of our waterbodies, Florida remains at the forefront of understanding water quality.”

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services did not grant repeated interview requests or provide a statement.

Earlier this year, a Times investigation found nearly 1 in 4 Florida waterways are tainted by forms of nitrogen, phosphorus or other issues that point to hazardous levels of the chemicals. Roughly half of polluted waterways analyzed by reporters saw increasing contamination over the last 25 years.

The pollution has fed enormous algae blooms that choke waterways, destroying seagrass beds and killing fish, including in Tampa Bay.

Gov. Ron DeSantis, after his first election in 2018, declared water quality to be among his top priorities. Since then, state leaders have steered hundreds of millions of dollars toward projects like upgrading sewage plants and replacing or removing old septic systems. The expensive efforts cover only a fraction of the billions experts say it will take to preserve Florida’s environment.

The governor, through a spokesperson, declined to be interviewed.

Much of the other work hasn’t resulted in the groundbreaking progress Florida leaders have sold.

Even as lawmakers revised rules to control urban and agricultural runoff, they doubled down on loopholes that reduce oversight of developers and farmers.

They also haven’t changed the foundational problem experts agree is behind the state’s approach: Polluters aren’t held accountable.

Your browser does not support the video tag. Runoff and septic pollution strain the spring-fed Homosassa River in Citrus County. ( DIRK SHADD | Times )

Florida’s mandate to reduce water pollution dates to the early 1970s, but state and federal officials practically ignored key requirements of the Clean Water Act until environmentalists forced their hand more than 25 years later.

The law left indirect pollution, from agriculture and urban sprawl, for states to handle. The goal was to restore as many of America’s waters as possible by mid-1983.

By 1998, hundreds of Florida waterways were still ailing. State regulators hadn’t written goals for cleaning them up — as required by the federal law.

Environmentalists sued the EPA for failing to enforce the Clean Water Act in Florida. They pointed to Lake Okeechobee, where pollution had been mounting for decades despite calls from scientists to address it. The threat wasn’t limited to the South Florida lake, the lawsuit said. Waters across the state were struggling.

The EPA settled the case by agreeing to force Florida to write precise goals for controlling pollution.

( DIRK SHADD | Times )

Florida says the goals are the “heart” of its approach to cleaning up dirty waters. But at the rate the state is going, writing the goals will take decades.

A recent report from a legislative research group estimated that the Department of Environmental Protection won’t finish the job until the end of the century.

When questions arise about the state’s slow progress, regulators note that complex science takes time. But another factor stalls momentum: pushback from polluters.

Activists again sued the EPA in 2008 to force Florida to follow the Clean Water Act. The state fought federal intervention side by side with industry groups, including the Florida Cattlemen’s Association, Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association, and the Florida Fertilizer and Agrichemical Association.

Bringing the case was like awakening “a war machine,” said Monica Reimer, an attorney who represented the advocacy organizations through the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice.

The debate centered on measures regulators used to determine whether waterways were too polluted. The EPA had asked states a decade earlier to develop numeric water quality standards to gauge impairment, but progress nationwide had been slow. The standards were more concrete than Florida’s existing ones, which considered waterways with visible harm — like seagrass losses or algae blooms — too contaminated.

Florida was working to create standards in the early 2000s but kept delaying, court records show. Seven years passed, with multiple blown deadlines, before the lawsuit triggered movement.

YOUR SUPPORT MAKES A DIFFERENCE

Wasting Away is based on more than a year of reporting born out of

more than 175 public records requests and an analysis of millions of data

points. It is work that no one has done before.

Projects like these are only possible with your support. Please

consider subscribing or making a tax-deductible donation to the

Times Investigative Fund.

For industry, the case threatened substantial change.

In response, the Associated Industries of Florida, one of the state’s most powerful business lobbying groups, created a task force to fight standards written by the EPA. Leaders from the state’s environmental and agricultural agencies regularly attended the meetings and offered feedback.

The task force pushed for an approach that exempted many waterways and required regulators to perform lengthy studies before determining whether water bodies were polluted enough to merit action.

Keyna Cory, who led the task force for Associated Industries, said she was proud of what the unusual coalition of major companies and government leaders accomplished. The group, she said, made people say, “Whoa, what’s going on here? You guys normally fight each other.”

Trade organizations and regulators united in attacking the EPA’s standards as scientifically flawed and said they would devastate the state’s economy amid fallout from the Great Recession. Politicians, including Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio and Democratic U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson, argued the measures would be too costly to Floridians and businesses. The fertilizer giant Mosaic said complying with the criteria would add more than $1.6 billion in expenses for the Florida phosphate industry, according to comments the company submitted to the federal government.

State officials further asserted that they had pollution under control.

They pointed to the Indian River Lagoon as a success. They boasted Florida was on the cusp of adopting stricter rules for urban runoff. They took credit for managing septic tank contamination. And they bragged that the state’s program to reduce agricultural pollution was aggressive.

The state’s arguments prevailed.

The EPA backed down, allowing Florida to adopt the rules it developed with industry groups — 15 years after the federal government first said states should establish the more protective standards.

Over the next decade, the Lagoon would become a mass grave for manatees. Hundreds of waterways would end up dangerously dirty. And the case Florida made to the federal government would ultimately fall apart.

Your browser does not support the video tag. Stormwater ponds, like this one behind a shopping center in Pinellas County, are a defense against runoff pollution across Florida.( DIRK SHADD | Times )

As Florida slow-walked protections for polluted waterways, the state experienced tremendous growth.

High-rises sprouted along coastlines. Subdivisions edged into the heartland. Cul-de-sacs of single-family homes overtook wetlands.

The building allowed Florida to welcome millions of people in the 1980s and ’90s who were drawn to the state’s famous waterways. But it came at a cost.

Many areas around polluted waterways saw dramatic growth. The largest share of those waters — from the St. Marks River near Tallahassee to Naples Bay — have been getting dirtier or haven’t been improving over the last 25 years, the Times found.

When developers turn natural land into buildings and concrete, they replace ground that absorbs rainfall with sidewalks and roads that expel it. The rain flows over waste, lawn fertilizers and other chemicals before traveling down stormwater drains and into waterways.

( DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times )

To secure environmental permits, contractors must show they have plans to manage contaminated stormwater at finished sites, generally by using state-recommended methods designed by engineers. Department of Environmental Protection officials review and approve some permits, but in many cases, the agency delegates those tasks to Florida’s five water management districts.

Businesses get a sweet deal once they’re permitted: Environmental officials automatically consider them in compliance with water quality standards. After properties are built, regulators assume the defenses are strong enough to keep waterways clean.

Developers most often use large ponds that hold dirty stormwater for treatment before it’s discharged through pipes and culverts into places like Tampa Bay and the Indian River Lagoon. Many ponds double as water features at apartment complexes, complete with fountains. Others are less noticeable, like grassy ditches that collect rain.

Florida has a history of botching oversight of the systems.

The state’s approach to runoff was developed in the early 1980s and was supposed to adapt and improve over time as science advanced.

But environmental leaders repeatedly ignored evidence and warnings that the state’s defenses weren’t protecting the water.

As early as the mid-1990s, Harvey Harper, a water quality engineer whose research firm has done contract work for the state, found problems.

A former official with the environmental agency, Eric Livingston, recalled pushing to get leaders to pay attention.

“There was really no desire,” he said.

As years passed, development boomed.

Builders turned more than 860,000 acres into sprawling suburbs, malls and streets by the late-2000s.

Then, Livingston hired Harper for a state-backed study. The 2007 report was damning: Instead of removing roughly 80% of chemicals, the most common methods often removed far less. One popular technique removed about half that amount.

“Once the report came out, then they couldn’t hide, because it was right there in black and white,” said Livingston, who served as chief of watershed management and led stormwater policies for the agency.

Soon, the department created a committee of state officials, technical experts and representatives from environmental advocacy groups and the development industry.

After two years of meetings, the state in 2010 published a draft of new guidelines but never adopted them.

“It was heartbreaking,” Harper said.

Six members of the committee told the Times that concerns about costs to developers and the election of Gov. Rick Scott appeared to stall the effort.

Florida’s economy was still reeling from the Great Recession, and stricter regulation was seen as a threat.

“I think the focus was all on economic recovery,” said Jeff Littlejohn, the environmental agency’s former deputy secretary for regulatory programs.

A decade passed.

Florida approved more and more development.

Scott remade the state’s environmental oversight. He laid off scientists and slashed millions of dollars from Florida’s water management districts. He aimed to speed up permitting and eliminated the agency once in charge of managing growth.

A spokesperson for Scott praised his environmental record but did not comment on why his administration did not move forward with the stormwater effort.

In 2020, after DeSantis became governor, lawmakers approved a landmark bill called the Clean Waterways Act. They promised unprecedented change for the state’s waters — including new rules for urban runoff. The Department of Environmental Protection again convened a committee, which picked up the shelved work from the earlier group.

Four years passed as members met and lawmakers debated the measures.

Then in early 2024, after 17 years of delays, lawmakers approved a stricter rule.

The effort strengthened parts of the law, adding a requirement that developers use modeling to show they will reduce chemicals as expected. It also implemented periodic maintenance requirements.

Kuchta, the environmental agency’s spokesperson, called the updates “a major step forward” in limiting pollution from urban runoff.

But the overhaul came with gaps and carveouts aimed at saving developers money.

“We are always playing catch up and all the while still developing in the same patterns that have gotten us in this predicament in the first place,” said Kim Dinkins, the policy and planning director for the advocacy group 1000 Friends of Florida.

“We are just continuing to make the same mistakes we’ve made for decades.”

What’s already built over millions of acres won’t have to change at all.

Properties undergoing redevelopment also won’t need to follow the most stringent requirements for controlling pollution. In cities, many projects fall under this category: An office space becomes a food hall; a shopping center turns into condominiums; a row of bars becomes a glitzy hotel.

Developers were given a long window to build before the stricter requirements go into effect this December — adding to the vast amount of construction that happened while the state knew its rules were flawed.

Regulators greenlit tens of thousands of permits from the time Florida learned its rules were deficient until the measures passed, a Times analysis shows. In total, land use data indicates more than half a million acres were transformed.

More than half a million acres of land were developed even after Florida discovered its methods for treating stormwater were flawed.

Developers built neighborhoods and installed dozens of stormwater ponds, from Belle Glade to Orlando, on land that drains to severely polluted Lake Okeechobee.

Families north of Tampa Bay moved into sparkling neighborhoods near Wesley Chapel and New Tampa as chemical levels rose in the Hillsborough River.

Around Silver Springs, developers transformed thousands of acres of grassland and forest into houses and hotels as contamination persisted.

Your browser does not support the video tag. In Hernando County, many homes around Weeki Wachee Springs State Park use septic tanks. County officials are trying to connect some of them to public sewers.

( DIRK SHADD | Times )

To build modern Florida, developers have relied on millions of septic tanks. They remain a cornerstone of the state’s growth, with builders putting in nearly 20,000 systems a year on average, according to a Times analysis of state data spanning roughly the last decade.

They’re packed into dense cities and suburbs, allowing condo towers, office parks and master-planned communities to spread over swampland without the cost or delay of building sewer lines.

But Florida’s greenlighting of cheap, rapid growth has left an estimated 2.6 million polluting septics — and homeowners largely on the hook to fix tanks as they age.

The state’s permitting program for septic tanks was long overseen by the Department of Health, but it has begun shifting to the Department of Environmental Protection.

Septics around contaminated Florida springs are responsible for about 5 million pounds of nitrogen pollution every year, according to a Times analysis of state estimates. Regulators in recent years have let builders add hundreds of tanks to vulnerable land across several springs, including Weeki Wachee, Homosassa and Wekiwa.

New rules require modern septics to be equipped to treat additional nitrogen near the springs and some other polluted areas, Kuchta noted.

Slimy algae is a constant at Weeki Wachee, said Rita King, a volunteer at the state park. The scene is a stark difference from the bright limestone the 79-year-old remembers seeing when she first performed as a mermaid in the famous underwater theater in the 1960s.

“It grows so fast, it smothers the habitats,” King said.

Septic pollution is not a new problem. As early as the 1970s, federal officials warned leaders in Dade County that the tanks around Biscayne Bay were “public health hazards,” releasing chemicals that fueled algae blooms.

Despite the county spending hundreds of millions of dollars on septic-to-sewer conversions, many tanks in the region remain.

They sit on about 100,000 properties around canals that drain into Biscayne Bay and are popular fishing spots. The waterways have shown some of the steepest increases in phosphorus levels across the state, an analysis of polluted waters shows.

Scientists and local officials encourage hooking up to public sewers because they’re more controlled, with treatment at central plants subject to permitting and monitoring. Even when traditional septic tanks function properly, they’re a major source of pollution.

Wastewater from toilets, sinks and showers gets flushed down drains and is carried by pipes to tanks buried in yards. Solids sink, building a layer of sludge that should get pumped out periodically. Scum, such as kitchen grease, rises to the top. Wastewater stays in the middle.

Laced with chemicals, the wastewater flows out of the tank into the earth. It trickles through filtering layers and soil, which remove some but not all of the nitrogen and phosphorus in the dirty water.

Polluted septic water mixes with groundwater. The contamination pushes into canals and bays and surges to the surface at springs.

Septic systems need ample dry ground so wastewater has time and space to soak into the earth before hitting groundwater. In built-out, soggy Florida, tanks often sit close together, just inches from the groundwater — without sufficient soil or modern technology to treat pollution.

Over time, the systems break down. Tanks and pipes crack. Drainage areas clog and flood the environment with barely treated wastewater.

Since the 1980s, technology to limit contamination has improved. But an estimated 610,000 properties in Florida have septics that are likely more than four decades old and could be past their effective lifespan — increasing the risk of pollution and malfunctions, according to a Times analysis of property data.

The Times identified nearly 250 contaminated waterways that are surrounded by properties on older systems. More of the waters have been getting dirtier instead of cleaner over the last quarter century, from tributaries of the Anclote River to Gemini Springs to the northern Indian River Lagoon.

The Florida Department of Health has spotlighted the threat to lawmakers. Health officials in a 2008 report said Florida could lessen environmental damage and protect public health by mandating regular inspections to identify broken systems.

Lawmakers have balked.

They passed a bill in 2010 to require inspections but undid it two years later.

Industry groups, including the Florida Home Builders Association, Florida Realtors and the Associated Industries of Florida, supported the measure that rolled back the law.

A Florida Realtors official told the Times in a statement his group supports “reasonable, periodic inspections” in certain cases.

Legislators who were against the inspection program argued it would make owning property more expensive in the aftermath of the Great Recession, costing outraged residents hundreds of dollars every five years, or thousands if their systems were failing.

Constantine, the Central Florida Republican senator who’d pushed for inspections, had warned his colleagues: “Pay a little bit now or all of us will pay a whole lot later.”

His warnings were ignored as pollution swelled in places like the Indian River Lagoon, which is surrounded by approximately 70,000 properties with septics, according to a Times analysis.

Eight years later, lawmakers declined to mandate inspections while working on their signature Clean Waterways Act. A panel of scientists convened by DeSantis had recommended them once more, but the bill’s sponsor thought the requirement would sink the broader effort.

In explaining the decision, Sen. Debbie Mayfield, R-Melbourne, used a common refrain in Florida: “We’ll get back to it.”

That hasn’t happened.

Lawmakers have focused on channeling millions of dollars to connect homes with septic systems to public sewers.

The work ahead is slow and staggering.

The city of Port St. Lucie has been trying to connect homes on septics to sewers for more than 25 years. It’s hooked up about 11,100, a spokesperson said, with just as many tanks still used in the city today.

Officials in Brevard County have started replacing septics but have estimated that connecting every property with tanks along the Indian River Lagoon could cost as much as $5 billion.

Pollution has already devastated the waterway.

A federal judge this year ruled that septic contamination has built up in the Lagoon, feeding algae blooms that decimated seagrass beds and left manatees to starve. The state has since appealed.

The judge originally sided with environmentalists who brought a lawsuit, ordering Florida regulators to temporarily stop permitting the systems around part of the Lagoon — determining that the state’s approvals contributed to the crisis.

Your browser does not support the video tag. Fisheating Creek in South Florida is surrounded by vast tracts of agricultural land. The creek drains to polluted Lake Okeechobee.

( DIRK SHADD | Times )

Outside heavily developed areas, millions of acres of cropland stretch across the state from peanut farms in the Panhandle to the sugarcane fields of South Florida. The industry serves a critical role in the country’s food supply as the second-largest producer of avocados, strawberries and oranges.

Together, the farms spread millions of pounds of chemicals from fertilizer and waste that could foul already tainted waterways every year.

Yet the state has collected little evidence that its methods for controlling farm pollution work, the Times found.

Since 1999, regulators have asked farmers to reduce pollution by following recommendations like applying fertilizer at times with less rain to wash contaminants away or irrigating frequently and in short durations to reduce runoff.

They’re known as “best management practices” and are rooted in research on good farming techniques. The logic, used by farmers across the country, is that tending to land efficiently will reduce environmental harm.

Florida’s program is run by the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, and the state’s environmental agency signs off on pollution controls.

Farmers with land near polluted waterways are required to take steps to limit contamination. But among those areas, the average participation rate in the state’s program is 53%, a Times analysis found.

Florida’s Agriculture Commissioner Wilton Simpson said farmers “should be ashamed” for not participating during a conference for landholders in 2024. The commissioner, a longtime egg farmer worth about $20 million, quickly reassured them about why.

“What we do there is we actually protect farmers,” he said.

( DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times )

Simpson is right that participating comes with big benefits. The state agrees to assume farmers are not violating Florida’s water quality standards, offers them funding for environmental projects and waives their liability should waterways become contaminated.

But the continued struggle of waterways surrounded by farmland casts doubt on the program’s effectiveness.

A Times analysis identified more than 100 that are contaminated, including Rainbow Springs, beloved by kayakers near vast tracts of pastureland; Lake Okeechobee, long a hotbed for dairy farms and cattle ranches; and tributaries to the Peace River, beside citrus groves and livestock companies.

In most of them, pollution levels haven’t been improving since the state’s program began.

Nearly half of the land draining to Fisheating Creek — a tributary to Lake Okeechobee where campers spot alligators and roseate spoonbills — is used for agriculture. Farmers who say they’re following the state’s practices have been doing so on most of the nearby land for at least a decade, the Times found, yet nitrogen and phosphorus levels have remained high.

Poor water quality has also prompted internal skepticism about the program.

In 2020, environmental regulators approved pollution control recommendations for cattle ranches — but underscored dangerous contamination in Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie rivers. Chemical levels were too high despite ranchers agreeing to reduce pollution, a letter memorializing the agency’s approval shows.

When water quality problems persist, regulators are supposed to reevaluate their approach.

But the Department of Environmental Protection typically wouldn’t do so until the state has finished sign-up efforts for the program, said Kuchta, the agency spokesperson.

“Which means they’ll never ever do it,” said Livingston, the former chief of watershed management for the department.

State leaders and industry lobbyists have said the program works because it’s based on science. But for more than 25 years, regulators have largely ignored their requirement to prove that the strategies reduce agricultural pollution from all products — dairy farms to vegetable fields.

“They write laws, and then they forget about them,” said Palmer, the biologist on the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute board.

The way to show success is simple: Test the water rolling off farms.

Regulators have only checked that their methods work in two instances: citrus groves in central Florida and the state’s timberland, records show.

They haven’t verified controls for several products that combined have a huge agricultural footprint across Florida.

More than half of the state’s farmland is used for grazing. Sugarcane, row crops and hay make up another fifth of Florida’s cropland, a Times analysis of agricultural data shows.

“They’re regulating with a blindfold on,” said Reimer, the former Earthjustice attorney.

The Department of Environmental Protection declined to answer written questions about why the agency hasn’t verified more methods.

Current and former department officials have said their efforts were hampered because agriculture companies won’t allow regulators on their land.

Livingston said he spent two years trying to find farmers who would let him test their water.

“It just never happened,” he said. “They did not want to have that data known.”

In recent years, lawmakers have said they’ve increased accountability on Florida’s farms. But agriculture lobbyists have told farmers they’ve protected the state’s lenient approach.

According to a Florida Farm Bureau white paper, the organization teamed with the Florida Ag Coalition — an umbrella group of farm companies and trade organizations — to help write the Clean Waterways Act.

The legislation spelled out an inspection process for the state’s agriculture agency. Regulators need to check farmers’ fertilizer records at least every two years to make sure they aren’t using more than the state recommended.

Soon after the law passed, farmers complained that the fertilizer limits were outdated and they needed to be allowed to use more.

Lawmakers later gave millions of dollars to the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences at the University of Florida to study and update the recommendations.

( LUIS SANTANA | Times )

The head of the institute, in a letter to Farm Bureau members, emphasized that the effort would benefit farmers.

“Science is supposed to support your bottom line, not take away from it,” J. Scott Angle wrote. “Scientists are doing the research to protect your profit and the planet.”

Angle told the Times the changes should carry environmental benefits by eliminating excessive fertilizer use that’s both expensive and harmful. The research is complicated, he said, and the goal isn’t to necessarily increase fertilizer limits but to adjust them so that farmers earn more money.

In his letter, he assured farmers the same. He didn’t mention water quality at all.

This story is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative. For more information, go to pulitzercenter.org/connected-coastlines.

About this story

After finding widespread contamination across Florida waterways, the Times wanted to understand the state’s system for regulating water pollution from indirect sources.

We interviewed over 140 scientists, regulators, lobbyists and environmentalists and analyzed millions of rows of data to illuminate state failures that have allowed rampant pollution from agriculture and development to persist.

Farmers, builders and real estate professionals hold considerable power in Tallahassee. To understand their political spending, we identified dozens of prominent industry organizations and companies that donate to political campaigns, largely through committees. We totaled all expenditures for each group, excluding transactions between them.

We also compiled all lobbying compensation reports from 2007 through June 2025. Lobbying firms are required to report a range of compensation. To be conservative, we added the lowest compensation amount in the range reported for each industry group or company.

We also examined trends in water quality and land use around struggling waterways to identify possible pollution sources. We used the Regional Kendall Test, a variation of a popular statistical test in environmental science, to conduct a trend analysis of monitoring data. (Analyses in this story built off our previous work, which determined pollution trends over 25 years in Florida.)

For each waterway, we defined surrounding basin areas, which are representations of land that may drain into the waterways. Tracking the flow of runoff is complex, and basins can be defined in many ways. Our analysis used a mix of state and federally-defined areas, which are ultimately estimates of watershed boundaries. Four experts reviewed our methodology and confirmed the validity of our approach.

To define basin areas in springs, we used Florida springsheds, which are determined by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. In lakes and springs without defined springsheds, we used the department’s planning units. For streams and estuaries, we used the National Hydrography Dataset, a nationwide system that delineates watershed areas, to determine immediate upstream basins.

To identify the footprints of agriculture and development, we used the National Land Cover Database. We also analyzed properties with septic tanks in each basin. We considered each unique parcel of land a property.

We considered basins to have dramatic growth if they fell into the top 25% of increases in development, measured by either raw acreage or percentage growth, around polluted waters that we analyzed statewide. Similarly, to identify waterways surrounded by the highest concentration of properties on septic tanks, we considered waterways that fell in the top 25% of septic tank concentration, measured by either the number of properties with tanks or the density of such properties per square mile.

To identify basins with high amounts of agricultural land, we considered waterways where at least one-third of the surrounding land use was agriculture. In all cases, the share of agricultural land was greater than other anthropogenic polluting land uses, such as development.

We considered the distribution of the data to identify these thresholds and consulted several experts on our approach.

Septic tank age was important to consider because the systems break down over time. We searched the Florida Water Management Inventory database, which compiles septic records at the property level from county health departments, to determine when tanks were installed. The database categorizes properties that are “known,” “likely” or “somewhat likely” to have septic systems. We counted all three categories in our analysis, which is consistent with approaches taken by state agencies.

We then used the database to determine the permit date for each property with a septic system. The date is not available in all cases, so we merged these records with Florida Department of Revenue property data, which indicates the year buildings were constructed. When the permit date was not available, we used the year built.

That allowed us to count the number of properties with septic systems that may have been installed before 1985.

The Times is continuing to report on water pollution. If you have

knowledge about the subject, our reporters would love to hear from

you: