When a Clearwater nurse was murdered by her ex-boyfriend after repeatedly asking for help from the police, the Tampa Bay Times set out to understand what went wrong.

What emerged was an example of Florida’s public safety system (stricken by ambiguous protocols and poor training) that could lead to domestic violence victims failing, even when individual executives are trying to help. That is especially true for victims of non-physical violence, such as stalkers.

This time spent over a year studying the system to identify gaps that would cause victims to be harmed despite their help reaching out for protection. It included hundreds of police records and departmental policies, research studies and reviews of state laws on domestic violence. More than 30 experts were interviewed, including law enforcement sources, training instructors and certified domestic violence resource center operators.

This is what we found.

1. There is more to domestic violence than physical abuse, but it is often overlooked.

Law enforcement officials often resort to physical violence to make arrests or act urgently to get the victim’s help. But experts say that it is not a good measure of risk.

An analysis of the murders of around 430 intimate partners over a decade in Florida found that lawyer and sociologist Donna King had four of the five murders without prior police reports of physical violence.

What came before was often threats, forced, stalkers.

2. Authorities will miss the murder warning sign if non-physical violence is minimized.

Florida law considers stalking a form of recent original domestic violence. But police and courts don’t always treat it that way. Unlike most physical abuse, stalkers can fly under the radar.

To claim someone who is stalking in Florida, you need to establish that multiple acts of intentional, malicious harassment, cyberstalking, or follow-up have occurred.

It may look like the threatening texts and the original driving around the victim’s office repeatedly. But it may also seem to leave a bottle of vodka on someone’s pouch in recovery. This is a more personal act designed to instill fear.

Separately, these events may seem trivial. However, law enforcement must identify larger patterns of abuse and listen to the fears of victims, said TK Logan, a professor at the University of Kentucky, has spent 20 years studying stalking.

Of the five victims killed by current or former partners, four had creeped up the previous year, one study found.

3. Sparse training in domestic violence puts both victims and police at risk.

By the time a person dials 911, they are already vulnerable. However, training requirements in Florida do little to ensure that responding officers are well prepared to navigate complexity.

Florida law requires that you complete six-hour training on certified domestic violence, besides duties in several other states, such as Arkansas (20 hours) and Missouri (30 hours).

To remain certified, officers simply complete retraining every four years. That training – 62 slides and 10 questions, multiple choice quiz – is far from comprehensive. For example, we do not define stalking, include an explanation of stalking behavior, or mention factors that put the victim in a greater risk. These include alcohol abuse, the presence of firearms, and recent relationships.

Want to break news in your inbox?

Subscribe to our free newsletter

You will receive real-time updates on major issues and events from Tampa Bay and beyond.

You’re all signed up!

Want more free weekly newsletters in your inbox? Let’s get started.

Check out all options

I finished my training and quiz in 23 minutes and got 100%.

“That’s not enough,” said Mark Wynn, a longtime law enforcement officer who consults about gender-based violence at the U.S. Department of Justice. “It’s a good way to hurt people by not understanding trauma and not understanding interpersonal violence.”

That includes responding officers.

A DOJ report, which analyzed officer deaths between 2010 and 2016, found that calling domestic conflicts or domestic-related cases was the most dangerous call for police.

4. Getting professional help to victims is important, but the policy to guide officers is insufficient.

It is unrealistic to expect individual police officers to advise victims through the nuances of the situation of domestic violence. Instead, the executive’s job is to safely separate the victim from the perpetrator, recognize patterns of abuse and arrest them.

It is also very important for executives to connect with experts who can help victims.

Florida has over 40 certified domestic violence resource centers, with trained experts in helping you submit legal documents, develop safety plans, and exploring emergency shelters. But if you don’t know that the victims exist, they are useless.

Florida law requires officers responding to domestic violence situations to connect victims with these resources. However, it does not lead to specifying how this occurs.

And for victims of domestic violence stalking (where they need to request repeated acts), their help is often withheld until multiple reports are filed, delaying access to potentially life-saving guidance.

For Clearwater nurse Audrey Petersen, a nurse at Clearwater, who was killed by her ex, police called the police three times before the officer handed her the victim’s rights pamphlet. The 17-page print, containing general information for all crime victims, included 15-page domestic violence hotline and numbers for the “spouse abuse shelter” (an outdated term for modern resource centers).

Sieve through pages of unrelated information is little instruction, and sieve through unrelated information is unreasonable, experts say. To help, some departments use simplified palm-sized cards with phone numbers and tips specific to domestic violence. However, there is little standardization. For example, victims seeking help in Tampa may receive different guidance and support than victims making similar calls in Miami.

5. Police often instruct victims to apply for a restraining order, but obtaining an order is difficult and dangerous.

In Florida, police are supposed to notify victims of domestic violence of their right to apply for an injunction. It is essentially a restraining order. These can give police clear evidence to get arrested.

But getting an injunction is not easy. Victims should explain their experiences in writing. The judge must then measure it against legal standards defined by the state. It is challenging for the average person and unfamiliar with the standards set by the law.

Simply filing for an injunction can inflam the abuser. “Like a bull with a red flag,” said Christina Lawrence, who leads Florida’s team of domestic violence cooperation lawyers.

That’s why it’s important for victims to connect with lawyers and advocates who can help them make decisions for their safety.

There are many different types of injunctions. Some victims may apply for a more general domestic violence injunction. Audrey Petersen, in Florida, has filed for a stalker injunction, unaware that this could be a more difficult path due to its vague definition and complex case law.

A Times data analysis found that over the last six years, most stalker petitioners in Pinellas Court were not protected prior to the hearing. That means people will be shuffled towards the court by the police, even if their petition is likely to be turned down.

6. Responsibility falls into victims to document their own experiences.

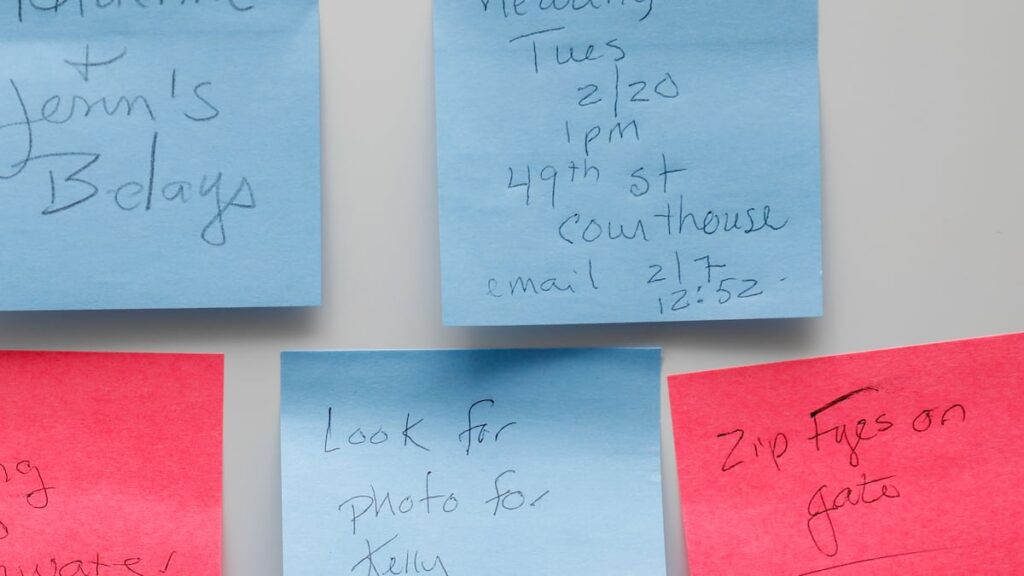

I met an incomplete system. It is important for people suffering from domestic violence to document their own experiences if they can do so safely. In many cases, victims are the best evidence of themselves.

Creating a timeline showing patterns of abuse and capturing photo and video evidence can help supplement reports to the police.

Too often, victims become obsessed with pursuits for protection and put a burden on the victims as they hear their fear, according to supporters. Experts said it shouldn’t have to be this way, but they were frankly realistic about insufficient resources and less burdensome systems. Ultimately, they said the victims could be left to dodge for themselves.

***

To get help around Tampa Bay

Pinellas County:

CASA (Suspension of Community Action Abuse) can be reached via the 24-hour hotline at 727-895-4912 and the online chat feature at Casapinellas.org. Walk-in is welcome at the Family Justice Centre, 1011 1st Ave. N, St. Petersburg.

Hillsboro County:

Tampa Bay Spring can be reached at 813-247-7233 24-hour hotline and thespring.org.

Pasco County:

Pasco County sunrise can be accessed on the 24-hour hotline at 888-668-7273 or 352-521-3120 and on the sunrisepasco.org.

If you are in danger right away, call 911.