EDITOR’S NOTE: This story contains graphic details of violence as well as explicit language. If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, you can call the Florida Domestic Violence Hotline at 800-500-1119. Additional resources are at the bottom of this story.

CLEARWATER — It was dark by the time Audrey Petersen got home, but a neighbor keeping watch said the coast looked clear. She disabled her security system and, pepper spray in hand, went to make herself a drink.

“No sign of him,” Petersen texted a friend as she mixed green tea with a shot of vodka. Her yellow Labs, Chewy and Digger, hovered near.

It had been two weeks since she’d called it quits with Frank and one week since she’d first called the police. She was 61, a pediatric nurse with laugh lines and strawberry hair. He was 71, a retired handyman from New York City. They’d been together 20 years, most good — or at least, not bad — but his drinking had gotten out of hand. Now, he was driving by at night, revving the engine of his jet-black Camaro, messaging that he missed her and that he’d never leave her alone.

Over the last seven days, Petersen had filed three reports with the Clearwater Police Department. At the urging of officers, she took a day off to apply for an injunction, essentially a restraining order. Petersen noted that her ex, Francis Scoza, had threatened her. She wrote that he had guns.

“No appearance of an immediate and present danger,” the ruling came back. To get the injunction, she’d have to offer more evidence or face Scoza in court.

“I am basically a prisoner in my home,” Petersen texted one of the officers.

As she settled in for the night on Feb. 9, 2024, Petersen wondered how she had found herself here, tiptoeing around the flower-filled abode where she’d prepped for countless Girl Scout meetings and puzzled over homework with her three girls from a previous marriage. She had followed authorities’ instructions, provided updates at every turn. Now she had to trust that the system would protect her.

In the days after the breakup, Petersen was adrift in dangerous waters. Scoza’s intimidation tactics should have sounded alarms — especially since stalking can be a warning sign for murder. Instead, those who could help moved too slowly to save her.

A little past 8 p.m., Petersen headed toward her backyard, where she liked to unwind. She walked past the big kitchen table, the mosaic of shimmering angels, the sticky note that reminded her to set the alarm when she came inside.

As she unlatched the back door, the winter air swept her cheeks and filled her lungs.

There was Scoza, dressed in jeans and a camouflage hoodie.

He was holding a gun.

A fatal miss

There are laws and tools designed to save people like Audrey Petersen. But they are of no use when authorities hesitate to intervene or overlook red flags.

Two weeks after she ended her relationship, after telling police over and over that the man she dated for decades was raging, drunk and armed, Petersen lay dead on her neighbor’s doorstep.

Her story showcases a lethal lack of urgency all too common in domestic violence stalking cases. It shows how police, saddled with insufficient training and vague protocols, can fail victims, even when individual officers are trying to help.

The Clearwater Police Department declined interview requests but responded to questions from the Tampa Bay Times by email. In a statement, Police Chief Eric Gandy called the death a tragedy and said officers worked off the clock to support Petersen.

“Unfortunately, the cycle of domestic violence is incredibly hard to predict, especially when there have been no previous acts of violence detailed in police reports or court petitions,” Gandy’s statement read. “The only predictable thing when it comes to domestic violence is the unpredictability of the offender.”

For decades, researchers have pinpointed clear factors that put victims at greater risk of being killed. Those include the presence of firearms and problems with substance use. The danger often surges when a person tries to leave.

From the moment a victim reaches out in the aftermath of a breakup, police need to respond with homicide prevention in mind, said Mark Wynn, a longtime law enforcement officer who consults on gender-based violence for the U.S. Department of Justice. To downplay that potential, he said, is to gamble with a person’s life.

Though making an arrest is the preferred response to domestic violence offenses, according to both state and Clearwater police policy, a department supervisor didn’t believe officers had enough evidence to apprehend Petersen’s ex.

Instead police ushered Petersen toward the civil court system to seek protection, a common step that can inflame abusers.

Then, when her request for a temporary injunction was denied, police told Petersen they would refer the stalking case to prosecutors.

That referral arrived at the State Attorney’s Office six days after her murder.

The department launched an internal investigation, which found that officers handling the case had followed protocol.

The report said the case didn’t rise to a stalking arrest, which hinges on repeated malicious and willful conduct. It cited “minimal” texts from Scoza and noted that “Petersen indicated that she did not want Scoza arrested.”

But the report leaves out vital context. About 48 hours before she died, Petersen told an officer she wanted Scoza to go to jail. When the officer said he would check with his boss and potentially make an arrest, Petersen thanked him.

“Whatever will make him leave me alone,” Petersen wrote. “This makes me so sad, but he needs to be stopped.”

None of that exchange is referenced in the investigation or police reports.

“This was a crime in progress, and her safety was at risk,” said Wynn, who trains dozens of police departments in domestic violence response each year. “The clock was ticking, and she was asking for help.”

Nothing left to give

Petersen had loved Scoza, she really had. His boisterous laugh, the way he held the attention of bar-goers with stories of yesteryear mischief and hustling. He was handsome, too — tanned skin, toned arms, eager smile.

They’d been introduced by a neighbor, a retired cop. Petersen was going through a difficult divorce, the kind of colossal heartbreak that shatters your sense of being. There was Scoza, a pledge of something new.

They balanced each other, in a way. Both loved company, but Scoza reveled in a life lived fast and loose where Petersen took comfort in a plan. She was the kind of person who’d invite a stray bartender to Thanksgiving, who’d carry a frozen bee inside to thaw. Scoza liked that Petersen softened his rough-edged world.

Though they never moved in together — he kept his condo in Dunedin, she kept her four-bedroom in Clearwater — he became family. At restaurants, he bragged to waitstaff about her kids, who were in grade school when they’d met. He drank his coffee from a mug, a gift from one of her daughters, stamped “UCF Dad.”

Petersen loved nothing more than being a mom. She’d spend weeknights sewing the girls matching sundresses, afternoons with a wildlife encyclopedia helping them ID the birds and snakes that skittered through the yard. Instead of calling something “weird,” she’d nudge them to think about what made it “interesting.” If you see someone struggling, she’d taught, you offer help. It was her heart that kept her with Scoza, even as he slipped away.

In the last year, Scoza had begun to feel more like a liability than a partner — an agent of chaos and mess. Petersen would come home from work at the children’s hospital to find him passed out on the doorstep, in the yard. Friends distanced themselves. One couple felt nervous having their son practice driving on the block, knowing Scoza’s Camaro could come flying around the corner, swerving over the curb before sputtering to a crooked stop.

Petersen’s daughters noticed the decline. It was almost as though his mind was melting. Stretches of coherence gave way to blurred reality.

They watched their mom fade. She didn’t camp anymore because he didn’t like to. She used to ride horses; now she hardly traveled. She’d head straight home from work instead of stopping by her daughters’ houses because Scoza didn’t like to be by himself.

No matter her attempts to get him help, no matter how many times he promised to change, she’d find him belligerent once more, often scratched or bleeding — badges of drunken falls.

On Jan. 26, 2024, she changed her locks. She told him she was sorry. She had nothing left to give.

She would survive, she told her friend Lisa Brewer three days later over salads and the din of NBA games at Norton’s Sports Bar. Scoza, she worried, wouldn’t fare as well. Then, as though summoned, he appeared at the restaurant’s door.

She could see it in his walk; he was drunk. He asked if he could join and made a fuss about paying their bill. Carefully, she asked him to give them space.

“Fuck you,” he spat. “Fuck you. Fuck you.”

Then he paid the tab anyway.

Rattled, Petersen typed a message to her daughters.

“If he reaches out to you, please don’t respond,” she wrote. “We are officially broken up. You have no relationship with him anymore.”

She typed a message to Scoza, too:

“Please leave me alone.”

“NEVER,” he replied.

‘Please help me’

Petersen’s neighborhood, where sparkling Audis lined manicured lawns, offered a reprieve from the county’s bustling corridor. She liked to lay out with friends by her pool and admire the butterflies fluttering through the garden — a sanctuary, tranquil and sweet.

Now a commotion ripped through the silence. Scoza was taking laps on the road along her back fence, revving so loudly that neighbors could recognize the sound.

Petersen didn’t want to call the police. In part, she feared it would set Scoza off. She wanted him to get help, not in trouble.

At the same time, she believed in the public safety system. When her daughters were little, she’d take them to the library for storytime with firefighters. She’d taught them that if you wanted something done in your community, you petitioned the city council. If you needed help, you dialed 911.

So on the evening of Feb. 2, 2024, Clearwater Police Officer Matthew Bremis listened as Petersen described the Camaro, the messages, her mounting anxiety. “You took 20 years of my life,” Scoza had sent in a text riddled with typos. “I’m not done. Be careful.”

In two years on the force, Bremis had won accolades. As a new recruit, the former college linebacker garnered praise for calming a 10-year-old girl with autism running through traffic. In 2023, a community group named him the department’s “Officer of the Year.”

“Petersen is worried for her safety after the separation and wanted a police report,” Bremis wrote in his case notes. Officers circled the neighborhood, he added, but hadn’t spotted Scoza’s car.

Stalking a recent ex is a form of domestic violence under Florida law. But police and the courts don’t always treat stalking as violence because the harm, unlike a bruise, can be less obvious.

When victims describe isolated experiences, like an ex driving past their home, it can seem trivial. It’s the job of law enforcement to identify the larger pattern, said TK Logan, a professor at the University of Kentucky who’s spent two decades studying stalking. Nearly four out of five victims killed by current or former partners were stalked in the prior year, one study found.

Law enforcement and the courts often rely on physical violence to act, but that alone is not a good measure of danger.

In an analysis of about 430 intimate partner homicides over a decade in Florida, lawyer and sociologist Donna King found that in four out of five murders, there had been no prior police reports of physical violence.

For Petersen, the first act was fatal.

A few hours after she talked to Bremis, she heard the hum of Scoza’s motor once more. She couldn’t see him in the dark, but the once-friendly sound had turned into a haunting.

He was back, she messaged the officer. Bremis said he could call Scoza.

“It may help. Or it may make him angrier,” she answered. “He’s tricky, but I feel you are able to pick up on that.”

Bremis gave him a ring. He told Scoza to take “a couple of days’ break from contact.” Scoza denied driving by.

Minutes later, Petersen’s phone lit up.

“You past the line,” Scoza texted.

She forwarded the message to Bremis.

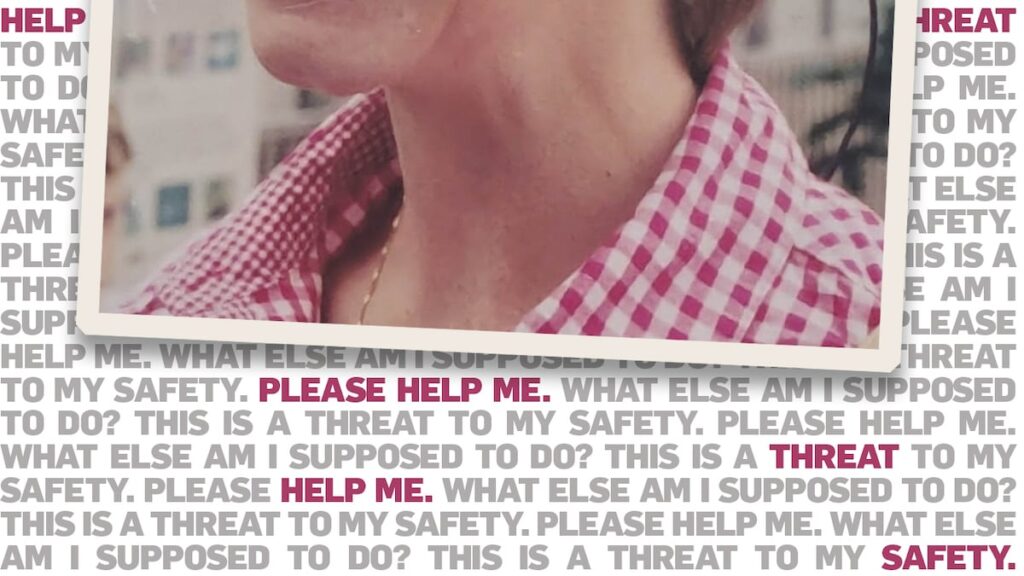

“This is a threat to my safety,” Petersen wrote. “Please help me.”

There was another way to keep Scoza at bay, Bremis explained. She could head to the courthouse.

A loaded gun

The winter sun was low the next day as Petersen waited by her neighbor’s door. She’d called police a second time.

“I just got a text from him,” she told the operator, trembling. “My three daughters’ names are Kelly, Michelle and Jenn, and he said, ‘Kelly, Michelle and Jenn are going to miss you. Bye.‘”

“I take that as a threat on my life,” she pleaded. Earlier, she explained, Scoza had pulled into her driveway and revved again.

She’d calmed down in the 30 minutes since, splashing water on her face to look presentable. But she wore worry like an article of clothing — her arms crossed, fingers rubbing the crook of her elbow. She’d been losing sleep, late to work twice in a row.

It was Bremis’s day off, so Officer Christopher Miller responded. The child of retired Clearwater police personnel, Miller had been on the force for about 16 years. He’d been celebrated for sleuthing out hundreds of carjackings — “an expert at hunting down stolen vehicles,” one story said. Now he listened to Petersen, once more, recount the events of the last several days.

Darlene Brown stood by for support.

Brown had come to know Petersen a decade ago while collecting information about the house she’d bought across the street. The previous owner, a 51-year-old nurse, had been killed there in 2014. Her boyfriend shot her in the master bathroom during a Sunday morning birthday party. In addition to murder, he was charged with using a firearm while drinking.

During the pandemic, when Brown was going through a breakup, the women grew closer. They’d walk the Countrypark neighborhood, Petersen offering an ear. Now it was Brown’s turn to hold Petersen up.

“I hate to say it, but he’ll probably do this again,” Miller told them. “Rev his engine just to kind of rile you up a little bit.”

Petersen nodded. “That’s what he’s doing, unfortunately, and I can’t let him know that he’s getting me upset,” she said.

“Right, yeah. You got to be strong,” Miller said. “Got to be strong.”

Brown, an elementary school math coach, drew her hands to her heart. She had spent many nights with Petersen and Scoza at the bar and had seen his descent into drunken, impulsive behavior. He’d bragged about roughing guys up — street fights when he was younger and skirting the cops in New York.

“I think that both of our concern is the fact that we know he owns firearms,” Brown said.

A year or so ago, Petersen explained, Scoza had fired a Mossberg shotgun inside his condo. Pellet holes scarred the wall. Nobody called the police.

“He told everybody he was just cleaning his gun. Well, you don’t clean a loaded gun,” she said. “I don’t have a gun — yet — but I know that.”

Miller told Petersen he would issue another warning. Meanwhile, she should go to court and get that injunction — like Bremis had advised the day before.

In Florida, police are supposed to notify certain crime victims of their right to apply for an injunction, a civil court order that requires one person to stay away from another. These can give police clear grounds to make arrests when violated.

But getting one isn’t easy. A victim needs to describe their experience in writing. Then a judge must measure that against legal criteria defined by the state.

It’s unclear whether Petersen knew, but Scoza’s ex-wife tried to get a domestic violence injunction against him in 2006. Records weren’t retained. The evidence was “insufficient,” and her request was dismissed.

In the face of an abuser fighting to maintain control, merely applying for protection can be dangerous — which Petersen worried over. But there is no requirement, when police tell people about the process, that they inform them of the risks.

And no records indicate that Miller or Bremis notified Petersen of domestic violence advocates who could help at this point.

As they talked through how to proceed, Miller, like Bremis, encouraged Petersen to call if she had more trouble with Scoza.

“In my opinion, he’s crossed into a criminal realm,” Miller said. Later, he added, “If he did it again, then I would just go arrest him.”

Her phone pinged with a text from Scoza. “P,” it said.

Was it a drunken misfire? Or, as Petersen worried, was it a symbol for “police” — a way to prove he was watching?

That evening, Miller dialed Scoza.

Again, Scoza denied driving by.

Again, he said he’d leave her alone.

Both were lies.

Cuts in the safety net

Often fraught with hard-to-prove allegations, denials and gray areas, stalking cases can be complicated. Scenes play out behind bedroom doors or in unrecorded calls, in late-night visits and coded threats.

An officer’s job is to safely separate victims from perpetrators, recognize patterns of abuse and make arrests. Advocates say that to expect individual officers to counsel victims through the nuances of the crime is unrealistic. The system wasn’t built for that.

That’s why it’s so important for police to connect victims to specialists, said Jacquelyn Campbell, a professor of nursing at Johns Hopkins University and a leading voice on domestic violence.

Many law enforcement agencies use a simple tool to help officers identify victims in serious danger: a questionnaire based on Campbell’s research called a Lethality Assessment Program. Under a recent law, Florida authorities must put it into use by 2027. On domestic violence calls, certain “yes” answers will set a victim on a path to get help, with referrals to resource centers that could, for instance, assist someone in making a safety plan.

Clearwater police had that tool but stopped using the questionnaire three years before Petersen’s death, according to a statement.

“LAP might have saved her life,” Campbell said. “It would have at least tagged her for increased risk and gotten her in touch with domestic violence services.”

Sparse training requirements add room for human error.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement requires all officers to complete a training on domestic violence every four years to maintain certification. That training — 62 slides — does not define stalking, include descriptions of stalking behaviors or mention risk factors, like alcohol. To complete it, officers need only click through the slides and pass a 10-question, multiple-choice quiz.

A Times reporter finished the training and quiz in 23 minutes and scored a 100%.

‘You know how chicks are’

Three days after Miller visited, Bremis arrived to take another report.

“I’m sorry, I don’t mean to be annoying,” Petersen said, greeting the officer at Brown’s driveway. “I just want to make sure you guys are on top of it.”

She mumbled to herself as she turned toward her friend’s house. The last week had brought on a wave of mental fog. She had asked her middle daughter, Michelle, to order her pepper spray. Petersen was once too nervous to let Michelle’s father keep firearms at home before they divorced. Now, she had asked for help buying a gun.

But there was an abashedness that washed over her when she picked up the phone to dial police again and again.

She’d told a friend she never thought she’d be a victim of domestic violence.

“Don’t worry about it,” Bremis assured her, his New England accent breaking through. “This is what we’re here for.”

Scoza, Petersen explained, had come by again — this time in the passenger seat of his drinking buddy’s BMW. Brown took pictures. The men made eye contact, then drove away.

The car, Petersen said, belonged to Alan Douglass, a broker. His friends called him “Roof,” a nickname supposedly earned after a fall off a building.

“Have you gotten an injunction order yet?” Bremis asked.

She hadn’t. The truth, she’d told Brown, was she worried he’d retaliate. But she also worried the cops would dismiss her if she delayed once more. She told Bremis she’d take off work the next day and file.

“And then if it keeps on happening and you want to pursue stalking charges, I think you have more than enough,” Bremis said.

He rang Douglass from his cruiser.

Why had he been driving by with Scoza? Bremis asked. Douglass didn’t answer. Then, slurring, he said they were visiting friends. He wouldn’t say who. He seemed to pretend service was cutting out.

“I have friends there. I have many, many friends there,” Douglass eventually said. “Everyone loves me, OK.”

He laughed.

“Everybody loves you,” Bremis echoed. “I gotcha.”

“Yeah, and you know how chicks are. They’re all drama, drama, drama, drama, drama, drama. Oh, someone’s trying to kill me. Blah blah blah blah blah,” Douglass said. “You know. You get it. Right?”

Douglass declined to comment, but on a brief call with the Times, he denied the interaction took place and declined the opportunity to review the recording.

Shortly after the men hung up, Bremis handed Petersen a victim’s rights brochure, which the state requires police give to crime victims. The packet, a 17-page print-out with information about the legal process and where to apply for an injunction, includes numbers for domestic violence hotlines and “spouse abuse shelters” — outdated terminology for the modern resource centers — on page 15.

“I spoke with him, Mr. Douglass. He’s not the best character, huh?” Bremis said.

Petersen’s eyes widened. “Oh good lord, what did he do?”

“He seems hammered,” Bremis said.

Later, he added: “I would definitely get the injunction.”

A ticking clock

She drove 9 miles south to the county courthouse, an imposing building off 49th Street.

In tidy handwriting, Petersen tried to condense the last two weeks, transcribing Scoza’s texts and summing up her fears on paper. At least she was one step closer to putting this behind her.

By late morning, she was home. Waiting.

“Part of my support system,” she texted Brown along with a picture of her dogs. “Yes, there is pizza involved.”

A couple hours later, a response from the court came back as boilerplate language on a standardized form.

Pinellas-Pasco Circuit Judge Doneene Loar had denied the request for temporary protection, it said. Soon, a summons would go to Scoza’s door, notifying him of a hearing Feb. 20.

“I guess the police officers will continue to get calls from me,” Petersen texted Brown. In her mind, it seemed like the judge was waiting for someone to get hurt.

“I’m shocked!” her friend responded.

When Miller checked in, he seemed surprised, too.

“Oh ok, even with the three reports?” he texted.

He asked if she wanted to press charges for stalking.

“I want Frank to stop. That’s all I want. I have been trying to follow procedure and have been calling out from work to deal with this. What else am I supposed to do?” she wrote.

Did she want Scoza to go to jail? Miller asked. She hadn’t before, he noted, but Scoza’s behavior had escalated.

“Yes. Please,” Petersen responded.

Though Miller had told Petersen he felt Scoza had veered into criminal territory, the officer wanted to cover his bases.

“I plan to speak with the on-call attorney tomorrow to make sure it would be a good arrest and if so, will find him and arrest him,” Miller wrote.

“Thank you,” Petersen replied. “Please try to get him help with his anger, drinking, all of it.”

Fault lines

For domestic violence victims, minute actions can be the difference between safety and disaster.

For Petersen, these fault lines were carved from inaction: the absence of services, the denial of an injunction, the failure to arrest. They emerged from a system ill-equipped to protect stalking victims in real time.

Police responding to domestic violence calls in Florida are required to advise victims of resource centers. In Petersen’s case, there’s no evidence officers went beyond handing her a general victim’s rights pamphlet after her third report.

If more help had been provided, her daughters said, Petersen would have taken every last recommendation.

A resource center counselor would have likely confirmed her gut fears and offered guidance, said Lariana Forsythe, chief executive officer of CASA, a certified domestic violence agency based in Pinellas County. Staff could have helped her decide whether applying for an injunction was right for her.

Stalking injunctions can be especially difficult to get in Florida because of murky definitions and complicated case law, said Karen Lasker McHugh, a Florida attorney who helps people petition for protection.

“A layperson is going to have difficulty satisfying all of the requirements,” she said.

A Times data analysis found that over a recent six-year span, most stalking petitioners in Pinellas courts did not get protection before a hearing — about six out of every 10 of them. That can mean people are shuffled toward court by police even when their petitions are likely to be turned down.

Clearwater officers did eventually connect Petersen with a department staffer who assists crime victims on Feb. 8, and they chatted by phone. But there was an apparent misunderstanding: The staffer filed a report noting, inaccurately, that Petersen’s injunction was granted.

Had that protection been in place, officers would have had cause to arrest Scoza, who made another pass by her house hours before he killed her. But it would be a dead end.

In a statement to the Times, Stephen Thompson, a spokesperson for the Sixth Judicial Circuit, said her application didn’t meet the legal bar.

“Ms. Petersen’s petition did not contain enough detail for the judge to determine there had been multiple episodes of willful and malicious acts which had no purpose other than to harass the petitioner, and which would cause the petitioner substantial emotional distress,” Thompson wrote. He noted that Judge Loar had granted Petersen a hearing to explain her case.

Because judges are barred from speaking with applicants prior to a hearing, these decisions can be challenging, McHugh said. Petersen’s death, she said, illustrates the precarity of an imperfect process.

Five attorneys briefed on the petition said another judge may have interpreted the situation differently.

Petersen’s petition outlined repeated harassment, stalking and threats, referencing three police reports and Scoza’s firearms, said Kristina Lawrence, who leads a team of attorneys for the Florida Domestic Violence Collaborative.

“This was an educated woman. This was a nurse. She provided a lot of information here,” Lawrence said. “I think some courts would have entered this injunction.”

Without it, Petersen’s hopes for immediate protection hinged on police action.

The department did not confirm whether Miller’s conversation with the on-call attorney happened. But as he told Petersen he would, he went to his boss, Sgt. Gary Bonzo, to see about an arrest.

His supervisor advised that he, instead, forward the case to the state attorney’s office to decide whether to prosecute.

But time was of the essence.

Feb. 9, 2024

It was 8:45 a.m. when a deputy knocked on the door to the second-floor condo and served Scoza the paperwork summoning him to court.

Scoza sat on the couch with a cup of coffee to look over the order. He lay the summons between an ashtray and the TV remote. Around lunchtime, he left for a bar about a mile from Petersen’s home.

By 12:44 p.m., he was so drunk that he was vomiting over the patio railing at Norton’s Eastside, but Douglass had just arrived. They ordered more drinks.

Sometime before 5, Scoza flopped into his Camaro and steered toward Petersen’s. It was around the time she’d get home, but she was still out, meeting fellow nurses for happy hour. While Petersen gushed about her daughter Jenn’s upcoming wedding, Brown was at Petersen’s letting the dogs out. She heard the roar of his engine and peeked over the fence.

It chilled her, seeing him there. He was pulled over with the window down, his elbow draped casually out the side, staring back.

Brown ran inside and called Petersen, but by the time she looked again Scoza had driven away — back to the bar for another drink alone.

He stayed until just before 8 p.m. Then he parked across the street, in the lot of a shopping center, pulled a gun from the car and walked the half-mile to Petersen’s house.

He hopped the fence, crawled through the doggy door of the screened-in pool and waited.

Left to bleed

The winter air swept her cheeks and filled her lungs.

There was Scoza, dressed in jeans and a camouflage hoodie.

He was holding a gun.

As Petersen ran, Scoza chased after her. She managed to dial 911 a final time.

911 Dispatcher: I have a caller on the mic. Her boyfriend broke into her house.

Petersen: NO! Frank!

Petersen tore through her house and made it to her next-door neighbor’s doorstep as Scoza fired. She screamed, then collapsed.

Petersen: He shot me. He shot me four times. I’m on the ground.

She wailed. Then, for a moment, it was quiet.

In the background, Scoza asked Petersen if she was still breathing.

“Fuck you,” he said, before firing again.

About a minute after she found him, Petersen lay at the step, taking gasping, gargled breaths.

Seconds later, Scoza lifted the gun to his head and pulled the trigger.

As sirens blazed, officers circled. Bremis saw her first.

“Victim right here,” he panted. “Goddamn it.”

He’d come from a day of traffic stops and accident injuries. Of conducting a welfare check and assisting another agency.

He touched Petersen’s neck. She was cold.

Several feet away, Scoza lay dead, but Bremis didn’t recognize him. He hadn’t met with him, not in person — no officer had. They’d only talked by phone.

“Shit, dude.” Bremis’s voice wobbled. “I’ve been out here the past fucking week.”

He told another officer she’d applied for an injunction. “But it got fucking rejected.”

Days later, a police report arrived at the State Attorney’s Office recommending the state bring charges against a 71-year-old Dunedin resident who had been stalking his ex-girlfriend.

The fighter

Not long before her death, between police calls and visits, Petersen bought herself a bundle of red roses. It was a nod to the Miley Cyrus song “Flowers,” about reclaiming independence in the aftermath of a breakup.

She’d play the track on an iPad propped on her kitchen counter and sing it on her commute.

Her daughters keep dried roses from that bouquet.

All of the little details about their mom, all the things they miss, are also the things that should have saved her life, Petersen’s eldest said.

Their mom was a fighter, Jenn Petersen said, but she fought by the rules — on paper or with words.

She was a meticulous, near-obsessive, record keeper. She kept every report card, every doctor’s note, every craft and receipt. Every week over a three-year period in the ‘90s, she wrote a letter to each of her girls. She stashed them by her bedside, a secret for when they were older.

Now, those memories are tinged with a burning fury.

After her mom’s death, Jenn said she went to the courthouse for a copy of the injunction petition. When she read it, she wanted to scream.

“The three police reports were right there,” Jenn said. “Did you not even look at the first fucking sentence?”

She feels like the police didn’t take her mom seriously — maybe because of her age. Why didn’t they arrest Scoza? Why wasn’t her mom given more guidance?

In the aftermath of a violent crime, Petersen’s daughters have learned, people tend to talk in inevitabilities. They say things like, “If someone wants to kill someone, a piece of paper isn’t going to stop them,” and “It all happened so quickly.”

But her daughters wonder: What is the point of these systems if not to give a person every opportunity to fight like hell?

“The police come after,” Michelle said. “The police always come after, and this was a chance that they had to come before, and they just didn’t.”

Nearly three weeks after Petersen’s murder, the department completed its internal review. In the investigation report, Sgt. Bonzo offered five reasons he’d counseled against an arrest.

The first, Bonzo told the investigator, was that Scoza had sent Petersen a “minimal number of text messages.”

Wynn, the consultant who trains police, disagreed with that premise. It’s the content that matters, he said, and that they were sent after Scoza was ordered to leave Petersen alone.

Contradictory instructions would have prevented Petersen from accruing evidence, anyway. At Bonzo’s urging, officers repeatedly told her to block Scoza’s cell. On Feb. 8, she told Miller she would.

“I basically had unblocked him so I could keep you informed if he tried to contact me,” she wrote.

Petersen had Scoza’s number blocked when he killed her. It’s unknown whether he tried to contact her that day.

The second reason was that on the night of her first police report, Petersen had only heard, not seen, Scoza’s car.

A third: The next day, when Scoza revved in her driveway, Petersen wasn’t home, Bonzo said. That’s not true. As Petersen told Miller, she’d been in the backyard when she heard the sound, and Brown called from across the street to say that Scoza was in the driveway. Either way, experts said, her whereabouts should be irrelevant — he was targeting her home.

A fourth reason was that Scoza didn’t stop or try to contact Petersen as he drove past with Douglass to visit supposed friends, the sergeant said. Going by the book, Scoza was free to pass by. But Petersen told police the men were lying — they didn’t have friends nearby. No reports indicate that officers followed up.

The final reason: Petersen “did not want to cooperate with charges.” But that was in the beginning. The report offered no further context.

Authorities must examine what went wrong after a tragedy like this, said Wynn, and make sure it doesn’t happen again.

“These are life-and-death situations,” Wynn said. “You can’t minimize. You minimize, people die.”

When Clearwater Police Cpl. Joseph May reviewed the case to identify policy and practice changes that could “prevent this type of tragedy,” he found a single issue of note: One of the officers had been keeping a running case log, instead of filing supplemental reports.

It was a paperwork error.

Times staff writers Teghan Simonton and Lesley Cosme Torres contributed to this report.

• • •

About this story

This story is based on more than a year of research and reporting. Tampa Bay Times enterprise reporter Lauren Peace reviewed over 5,000 pages of documents and interviewed more than 30 people about Audrey Petersen’s case to recreate the two weeks leading up to her death and to identify points of missed intervention.

Details about Petersen’s interactions with law enforcement came from various records and transcripts from the Clearwater Police Department, the Pinellas-Pasco State Attorney’s Office and Pinellas County courts. Those include hours of video captured on body-worn cameras, audio from 911 calls, hundreds of pages of police records — including case notes, photos, emails and activity logs — and more than 50 texts between Petersen and officers.

The Times reviewed the Clearwater Police Department’s policy handbook, as well as Florida statutes on domestic violence, dating violence, stalking and officer investigations to identify ambiguity in protocol and state law.

To understand risk factors for fatal violence, Peace combed through research studies on domestic violence and spoke with experts who included medical professionals, lawyers, law enforcement officers, training instructors, victim advocates, criminal justice scholars and certified domestic violence resource center operators.

• • •

To get help around Tampa Bay

Pinellas County:

CASA (Community Action Stops Abuse) can be reached on its 24-hour hotline at 727-895-4912 and via an online chat feature at casapinellas.org. Walk-ins are welcome at the Family Justice Center at 1011 1st Ave. N in St. Petersburg.

Hillsborough County:

The Spring of Tampa Bay can be reached on its 24-hour hotline at 813-247-7233 and at thespring.org.

Pasco County:

Sunrise of Pasco County can be reached on its 24-hour hotline at 888-668-7273 or 352-521-3120 and at sunrisepasco.org.

If you are in immediate danger, call 911.

• • •

If you or a loved one is experiencing domestic violence

Domestic violence is about maintaining control, and you are entitled to help even if the abuse has not become physical. Abuse, experts say, can include controlling your money, isolating you from friends and family, and making threats or actions designed to instill fear.

The most dangerous time is often when a victim exits the relationship, according to experts. Advocates can help make a plan to stay safe that considers your individual circumstances, free of charge. Call or message a local certified domestic violence resource center to consider your options or seek emergency shelter.

Experts advise documenting your experiences to the best of your ability, if it is safe to do so.

If you are seeking an injunction, you can ask for legal help on site when you fill out your application, and lawyers are available to assist at no cost.