By Michael Lietke, Associated Press

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) – The Internet is not the same without a similar button, a thumb icon that Facebook and other online services have transformed into digital catnip.

Like it or not, the button served as a creative catalyst, dopamine delivery system, and emotional batter rum. It also became an international tourist attraction after plastering symbols on a giant sign that stood outside its Silicon Valley headquarters until Facebook was rebranded as a meta platform in 2021.

The new book, Like: The Button that The World, delves into the complex narrative behind the symbols that become both mana and bain in a digitally driven society.

It’s a tale that traces back to gladiator battles for survival during the Roman empire before fast-forwarding to the early 21st century when technology trailblazers such as Yelp co-founder Russ Simmons, Twitter co-founder Biz Stone, PayPal co-founder Max Levchin, YouTube co-founder Steve Chen, and Gmail inventor Paul Buchheit were experimenting with different ways using the currency of Recognition To give birth to people to post engaging content online for free.

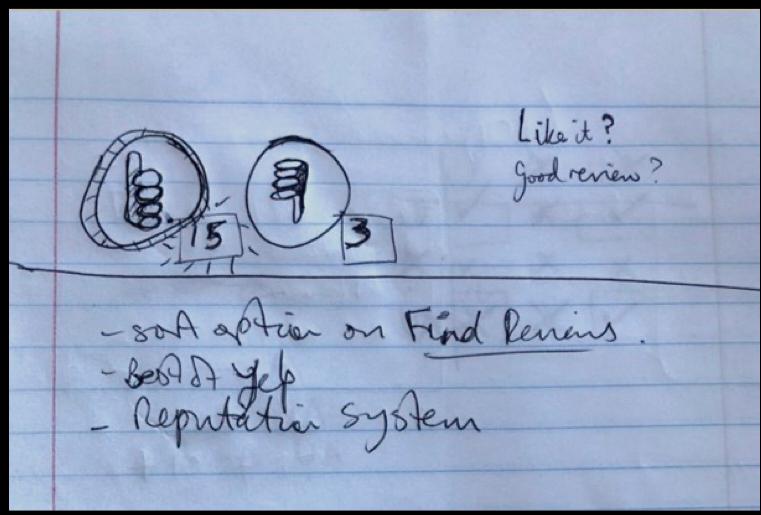

As part of that noodles, a Yelp employee named Bob Goodson sat down on May 18, 2005, drawing a rough sketch of a thumb as a way for people to express their opinions on restaurant reviews posted on the site. Yelp took the proposed symbols of Goodson, instead using the “convenient”, “funny”, and “cool” buttons that Simmons has come up with. However, the discovery of that old sketch encouraged Goodson to work with Martin Reeves to explore how the Like button turned into their new book.

“I like you, I like your content, and I’m like you. I like you, I’m like you, I’m part of your tribe.” “But it’s very difficult to answer simple questions.”

Social wells behind social symbols

Facebook is the main reason, but similar buttons have become ubiquitous, but the company hasn’t invented it, and has almost threw it away. Five years after the creation of the social network in Harvard dorm rooms, it took almost two years to overcome the solid resistance by CEO Mark Zuckerberg before finally introducing symbols to its services on February 9, 2009.

Like many innovations, buttons of the same kind were necessarily born, but they were not the brainchild of one person. The concept became popular in Silicon Valley for over a decade before Facebook finally accepted it.

“Innovation is often social and Silicon Valley was the right place for all of this because this has a culture of meetups, but that’s not the case now,” Reeves said. “Everyone was getting together to talk about what they were working on at the time, and it turns out that a lot of them were working on the same thing.”

Efforts to digitally express approval or create simple mechanisms to disappoint or express approval from the sources of online services such as Yelp and YouTube will succeed in the ability to post commentary and videos that will help make your site even more popular without spending much money on content. That effort required a feedback loop that didn’t require many hoops to navigate.

The role of Hollywood in Button’s Saga

And as Goodson was putting his thumb up and putting the noodles in a falling gesture with his thumb, it didn’t come out of the vacuum. The technique of signaling approval and disapproval was led into the 21st century zeitgeist by the Academy Award-winning film Gladiator. There, Emperor Commodos, painted by actor Joaquin Phoenix, was portrayed – using either the arena spared or killing combatants.

However, positive emotions recalled by the date of thumb in popular culture, thanks to the 1950s character Fonzie, played by Henry Winkler in the top 1970s television series Happy Days. Gestures became a way to express joy programmatically through the remote control buttons on digital video recorders created by Tivo in the early 2000s. At about the same time, the site asked for feedback on the looks of people who share their own photos, whether hot or not – was playing around with ideas that would help stimulate buttons like buttons, based on book research.

Others who contributed to the pool of useful ideas include the pioneering news service Digg, blogging platform Xanga, YouTube, and another early video site Vimeo.

Big breakthrough in buttons

However, Facebook undoubtedly turned the like button into a universally understood symbol, while benefiting most from the entrance to the mainstream. And it hardly happened.

By 2007, Facebook engineers were tinkering with similar buttons, but Zuckerberg feared that the social networks were already messy, and Reeves said, “He would actually be considered trivial and would make the service cheaper.”

However, FriendFeed, a rival social network created by Buchheit and now Bret Taylor, now Openai Chairman Bret Taylor, did not have that uncertainty and unveiled its own button in October 2007.

However, the buttons were not as successful as they left the lights on in FriendFeed, and the service was obtained by Facebook. By the time the transaction was finished, Facebook had already introduced a similar button – only after Zuckerberg rejected the first idea of calling it a great button “because it’s not as great as great,” according to the book’s research.

After Zuckerberg became tolerant, Facebook not only made it easier for viewers to engage with social networks, but also facilitated the individual interests of people and gathered the insights needed to sell targeted ads, which accounted for the majority of last year’s $165 billion metaplatform. The success of this button encouraged Facebook to go further by allowing other digital services to infiltrate it into the feedback loop, adding six more types of emotions in 2016.

Although Facebook has not released the number of responses it has accumulated from Button and other related options, Levchin told the book’s author that he believes the company has probably recorded trillions of those. “The content that humans like is probably one of the most valuable things on the internet,” Levchin said in the book.

Similar buttons have created a trend in emotional issues, especially among adolescents. They feel that if their posts are ignored, they are telling the narcissist who easted positive feedback. Reeves said these questions were, “How can we predict side effects and interventions if we cannot even predict the beneficial effects of technological innovation?”

Still, Reeves believes he slammed his own human with the buttons that were combined to create it and the powers that were combined to create it.

“We thought the serendipity of innovation was part of the point,” Reeves said. “And we don’t think we can get bored of robbing preferences and comp-meme abilities so easily, as it is a product of 100,000 years of evolution.”

Original issue: May 16, 2025, 3:08pm EDT