TAMPA — The crime was notorious and extraordinary.

The victims: a mother and her two teenage daughters vacationing from Ohio, their bodies found one morning in 1989, bound and weighed down with concrete blocks in the waters of Tampa Bay.

The ensuing murder investigation was unlike any other by local law enforcement. The eventual arrest and conviction of the killer became a point of pride for the many investigators who worked the case, most especially the St. Petersburg police detectives.

So when a retired FBI agent published a book in late 2023 in which she wrote of having played a key role in solving the case, retired cops took notice.

Jana Monroe, a former FBI agent, had little involvement in the case, the investigators contend. Yet, in one 11-page chapter of her memoir, “Hearts of Darkness,” Monroe discusses the case and portrays herself as having been deeply involved in the investigation from the beginning. She takes credit for motivating local police to pursue the evidence that ultimately led to the killer.

Her account contradicts memories of those who worked the case locally. They were so troubled that they brought their concerns to the St. Petersburg Police Department, which last year sent a letter to Monroe’s publisher and her attorney.

The letter expressed concern that Monroe was “overstating her involvement and contributions” and alleged inconsistencies between her account and what’s reflected in police records.

“While the department is certainly grateful to Ms. Monroe for her minimal assistance with the case, it was due to the combined effort of many individuals … that this case was ultimately solved,” the letter stated.

Monroe’s attorney, John Gatti of Los Angeles, later sent a brief reply, saying the department’s letter “contains inaccurate references that mischaracterize Ms. Monroe’s FBI work.” He did not elaborate.

Reached by phone, Monroe told a Tampa Bay Times reporter she knew of the investigators making claims about her book and called it “unfortunate.”

“I think the problem is I have more of a memory of this than they do because I took such copious notes,” she said.

Those who spent much of their careers in solving the case take offense to Monroe’s account. The historical record, they say, is being distorted.

“They believe that she is taking credit for work that they did, and they have a certain amount of outrage,” said Jim Ramey, a retired FBI agent and former St. Petersburg police officer who assisted in the investigation and helped present the case to the agency’s behavioral science unit. “There’s a real sense of injustice here.”

The Rogers murder case

The murder investigation began the morning of June 4, 1989. The bodies of Joan Rogers, 36, and her daughters, Michelle, 17, and Christe, 14, were found at different locations in Tampa Bay, close to St. Petersburg. They were nude below their waists and had ropes attached to concrete blocks around their necks.

Want breaking news in your inbox?

Subscribe to our free News Alerts newsletter

You’ll receive real-time updates on major issues and events in Tampa Bay and beyond as they happen.

You’re all signed up!

Want more of our free, weekly newsletters in your inbox? Let’s get started.

Explore all your options

The family had driven from their Ohio dairy farm for a weeklong Florida vacation. Their Days Inn motel room off State Route 60 had been abandoned. Their car was found parked at a boat ramp along the Courtney Campbell Causeway.

The investigation lasted three years and culminated in the arrest of Oba Chandler, an aluminum contractor with a criminal history. Chandler was convicted and sentenced to death. He was executed in 2011.

The story was the subject of the St. Petersburg Times narrative series “Angels & Demons” by Thomas French, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1998.

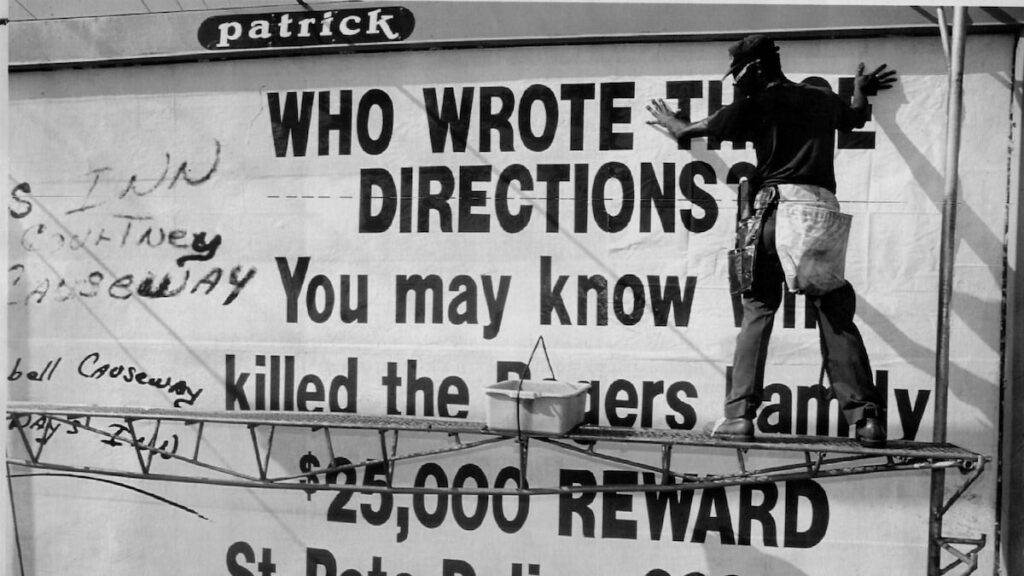

Part 4 of the series documented how police released images of an unknown person’s handwriting, taken from a brochure found in the Rogers’ car. One of Chandler’s neighbors recognized the handwriting as his. She also believed he resembled a composite sketch of a suspect in the rape of a Canadian tourist in Madeira Beach, which was similar to the Rogers’ case. Her tip ultimately put police on Chandler’s trail.

Jana Monroe spent more than two decades in various roles with the bureau. In her book, she writes about time spent assigned to the FBI’s Tampa field office in the late 1980s, and how she joined the behavioral science unit in the early 1990s. She led the cyber division shortly after its creation following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, serving as an assistant director for the agency. Her name was mentioned as a possible successor to former FBI Director Robert Mueller.

A single chapter of Monroe’s book discusses the Rogers case. Titled “Thinking Big,” it includes a criminal profile of the then-unknown murderer and recommendations that were made to St. Petersburg police detectives, including advice to enlist the media to publicize the case, in their efforts to identify the killer. Monroe helped create the profile in 1991 in her job with the FBI’s behavioral science unit.

Monroe writes that she was standing on a dock the morning the bodies were brought ashore. At one point, she mentions a report from two Canadian women about having been physically assaulted while on vacation in Florida, similar to the Rogers’ case. She writes that a follow-up visit from investigators “put an end to that.”

She later discusses the handwritten directions that investigators found in the Rogers’ car. She writes that the notes were “the only and very slim clue we had to go on,” and that investigators believed the handwriting was that of Joan Rogers.

She quotes a conversation with unnamed St. Petersburg police detectives in which she asks if they’d compared the notes to samples of Joan Rogers’ handwriting and whether they’d asked her husband if the writing was hers. She also writes it was her idea to feature the handwriting on billboards in the Tampa Bay area, to see if the public might recognize the penmanship.

“Within 48 hours,” Monroe writes, “calls had come in from two unrelated people, both naming Oba Chandler as the writer of the directions.”

‘Astonished’

The people closest to the Rogers investigation were “astonished” at Monroe’s account, said Ramey, the retired FBI agent.

Contrary to what’s in the book, multiple people involved in the case told the Times they have no memory of her being there the morning the bodies were brought to shore.

A portion of the St. Petersburg police report, provided to the Times, includes lists of the investigators who went to the U.S. Coast Guard dock the morning the bodies were discovered. The documents name personnel from the St. Petersburg and Tampa police departments, the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office, the Florida Marine Patrol, local firefighters, prosecutors and a medical examiner. No one from the FBI is listed.

“She was not at the dock,” said Glen Moore, the retired St. Petersburg police homicide sergeant who oversaw the Rogers investigation. “There’s no evidence that she was at the dock. No one saw her there.”

The investigators also took issue with Monroe’s account of the conversation about featuring the unidentified handwriting on billboards.

“She’s making it sound like the St. Petersburg Police Department were a bunch of inept people,” Moore said. “Making us sound like a bunch of buffoons, yeah, that hurts.”

The idea to put the handwriting on a billboard did not come from Monroe, the investigators said. News accounts at the time credited former Pinellas County Commissioner Barbara Sheen Todd with the idea.

Todd, in a recent interview with the Times, said that she was so disturbed by the murders, having three daughters of her own, that she indeed suggested to police that they might solicit tips by placing the writing on billboards. When told they had no money for billboard space, Todd said she worked a connection with a local advertising company to make it happen.

After Chandler was arrested, Todd said, the police invited her to a ceremony and awarded her a plaque. But she insisted the case’s resolution was the result of the work of the St. Petersburg police.

She, too, took offense to what Monroe wrote.

“She’s obviously very creative,” Todd said. “It’s not the truth. I respect anyone who’s a writer. I like to write myself, but I don’t think it’s right to claim something that’s not true.”

Todd is also mentioned in French’s “Angels & Demons” series as the person who suggested putting the handwriting on billboards. French said he didn’t start reporting on the case until after Chandler’s arrest, but he has no reason to doubt what the retired investigators say about Monroe’s work.

“They’re not show-boaters,” French said. “They’re straight shooters.”

Craig Pittman, who covered the Chandler case for the Times as a courts reporter in the 1990s, recalled that the FBI’s involvement was limited, and the profile of the unknown killer wasn’t especially helpful in solving it.

“Everybody wants to claim victory,” he said. “The fact is this case was solved by one of Oba’s own neighbors.”

In any case, news accounts state that Chandler’s neighbor saw the writing in the newspaper, not a billboard.

A retrospective story that Pittman co-wrote in 2011, shortly before Chandler’s execution, states that the neighbor, Jo Ann Steffey, realized a year after the murders that Chandler resembled the composite sketch of the suspect in the rape of a Canadian tourist who had been assaulted by a man on a boat in Madeira Beach. The rape would later become a key element in the Rogers murder case.

It took a long time for Steffey’s many tips about Chandler to reach investigators. Weeks before the handwriting went up on a billboard, she and a fellow neighbor faxed to investigators samples of Chandler’s handwriting from documents he’d signed while doing work in the neighborhood, the 2011 story states.

Monroe, the investigators say, didn’t become involved in the Rogers investigation until 22 months after the murders. Even then, they say her involvement was limited to helping create the profile of the killer. After Chandler’s arrest, she provided advice about interrogation techniques police could use to get a confession. Chandler, however, did not speak with them.

Cindy Leedy, one of the case’s lead detectives, said the profile led the investigative team to broaden the interviews they conducted to include police officers, firefighters, delivery people and others who would be considered trustworthy. Ultimately, though, the profile wasn’t a key to cracking the case.

“I don’t know why she would write things like that,” Leedy said. “I’m sure her career was interesting enough without taking credit for things she had nothing to do with.”

Responses

When reached recently by the Times, Monroe mentioned that her involvement in the Chandler investigation was not in an official capacity but as a “coordinator.”

She referred questions to Gatti, her attorney, but he did not respond to multiple subsequent emails and voicemails from the Times seeking comment.

A spokesperson for the FBI in Tampa said federal privacy law prohibited them from commenting on or confirming Monroe’s employment. A Freedom of Information Act request for documents detailing Monroe’s involvement in the Chandler case remains pending.

Her memoir isn’t the only place where Monroe’s account has appeared. The 1995 book “Mindhunter,” by legendary FBI profiler John Douglas, gives an account of the Chandler case that credits her with the billboard idea, consistent with Monroe’s telling. A representative for Douglas said he was unavailable to be interviewed for this story.

Yet, those closest to the case remain unconvinced.

Doug Crow, the former Pinellas County prosecutor who led the case against Chandler in court, sent a 14-page letter detailing his memory of the case last year to St. Petersburg police Chief Anthony Holloway and Assistant Chief Mike Kovacsev. He wrote about discrepancies in Monroe’s account. He mainly wrote, though, to “defend the diligence and competence” of the police officers “who were responsible for bringing Chandler to justice.”

After that, the department reviewed its own records and wrote to Monroe’s publisher. Kovacsev, who drafted the letter, said he understands the frustration the investigators feel, as the Chandler case meant a lot to so many.

“I do feel their pain,” Kovacsev said.