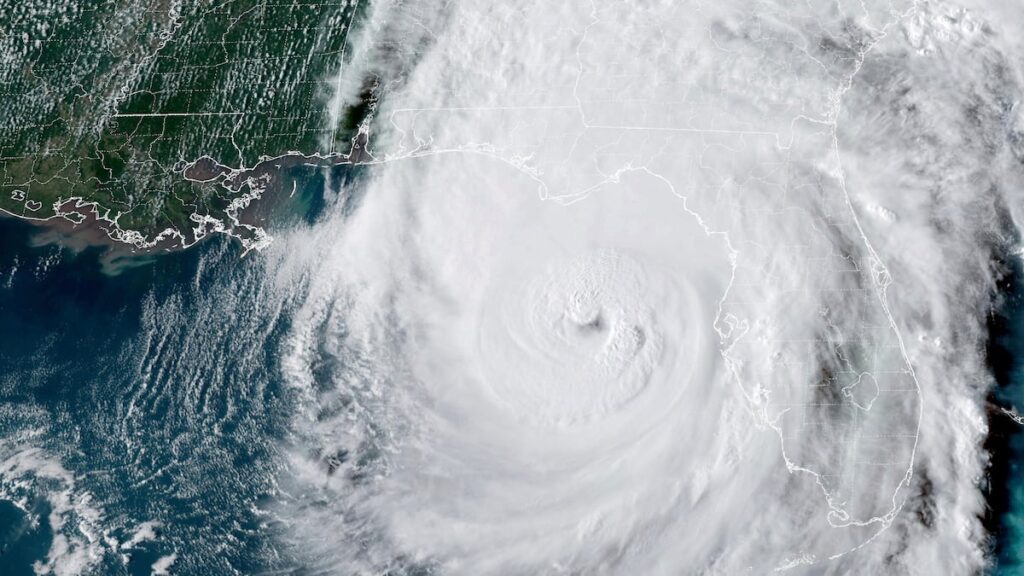

Two weeks ago, more than 40 Americans were killed in fires and tornadoes in Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Kansas, Texas and Missouri. Last Wednesday, President Donald Trump issued an executive order on “achieving efficiency through national and local preparation” in disaster recovery and resilience. Devastation from the storm is a reminder of how high the interests of disaster recovery reform are in an era of increasing disasters.

Importantly, the administration has stepped away from the position that “FEMA should be removed as it exists today,” and instead adopted the reform strategy advocated by Louisiana representatives Steve Scullies and Troy Carter.

As a former manager of a federal emergency management agency, I agree that disaster recovery reform is the right approach. Maintain parts of the system that are operating, provide better service to survivors, spend money efficiently, fix broken things to enhance national resilience in the face of more disasters.

This is what it works. First, FEMA is uniquely suited to coordinate government-wide responses during the immediate post-disaster period. Based on weather reports from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, FEMA will move water, food, medical supplies and generators to the staging area to allow for rapid distribution after a storm. We will deploy teams within hours of the incident being launched to support state and local emergency business operations. The city and search and rescue teams save lives in collapsed buildings, floods and other extreme circumstances.

Second, FEMA has already taken a risk-based approach to creating grants for a wide range of preparation and resilient activities using the national risk index tool. FEMA building’s resilient infrastructure and community grants help local governments make important investments in their resilience. Third, states and local governments will resort to larger federal governments to reimburse local spending to bring children back to school and ensure people can work safely.

There is no reason for individual states to develop this kind of ability and pay. Spreading disaster risks and costs across the country is a good and efficient policy that will make the whole country stronger.

Spend your days with Hayes

Subscribe to our free Stephenly newsletter

Columnist Stephanie Hayes shares thoughts, feelings and interesting business with you every Monday.

You’re all signed up!

Want more free weekly newsletters in your inbox? Let’s get started.

Check out all options

However, you cannot ignore the parts of the system that require fixation. Survivors have poor customer service experience when applying for assistance, project costs are too high, and state and local governments are not revived enough to reduce recovery costs. As the administration is considering ways to reform disaster preparedness and response, it should focus on three areas.

First, we need to improve the customer service experience for survivors. FEMA’s programs, which support individual households, account for a small share of total disaster spending, but have a major impact on its reputation. The maximum grant award you can currently receive for housing assistance is $43,600. But after a disrupted cycle of rejection and appeal, the majority receive only thousands of dollars. Customer service experience and a significant simplification of these programs – potentially Block Grant Style programs to families need to ensure that survivors can predict how much federal assistance they will receive to supplement insurance, charity and private resources, and how long they will be able to obtain federal support.

Second, the administration must make changes to FEMA’s public assistance program to reduce administrative costs and increase predictability for state and local governments. FEMA currently uses huge talent to manage its program on a refund basis. State and local governments spend money on repairing schools, roads, or water treatment facilities and submit receipts for refunds. Some of these projects have been extended over decades beyond disaster events.

FEMA can create block grant programs for projects that are under $10 million and projects that have been featured in the book for many years. In these projects, in jurisdictions, you can simply estimate the cost of the project and complete it to receive grants from FEMA. Teams should be empowered to negotiate with state and local jurisdictions to estimate the cost of completing an old project, then issue grants to close the project. This program should come with a powerful audit program with new technology to ensure that you spend your money as intended.

Finally, there is no doubt that states facing ongoing disaster risks must step into the plates when reducing disaster costs. Knowing that FEMA picks up the tabs, there is no excuse for local jurisdictions that cannot carry insurance to public buildings. The federal government needs strong local partners to ensure that US taxpayer dollars are not dumped in an affordable reconstruction cycle. The state legislature should show that they can become strong partners by allocating funds for insurance, recovery and resilience, but will update building standards and land use policies to reduce damage from repeated disasters.

Without fixing the system, disaster survivors will lose faith in local, state and federal leaders. Communities that don’t get help after a disaster will soon experience a downward economic spiral that leads to poverty and evacuation, forcing families to migrate, businesses shut down, and worsen the entire neighborhood. Over time, these regions will struggle to recover at all, leading to declining populations, increasing unemployment and long-term social instability that weakens the fabric of our country.

These are problems and solutions that have been talked about for a long time within FEMA. What is missing is the political will to accomplish them. President Trump and his team are willing to take bold steps to cut costs. With less than 90 days of hurricane season, we demand that America and local governments lead the way, backed by federal powers, after the inevitable disaster.

Craig Fgate served as FEMA administrator under President Barack Obama and Florida’s Director of Emergency Management under Gov. Jeb Bush. Peter Gayner served as FEMA administrator for the first semester of President Donald Trump, director of Rhode Island’s Emergency Management Agency, and served as Lieutenant Colonel in the Marine Corps.