Peter C. Earl

The Trump administration’s announcement on a 10% tariff on Chinese imports and a 25% tariff on goods from Mexico and Canada has resulted in considerable volatility in the stock and foreign exchange markets.

Naturally, investors have expressed concern about the macroeconomic implications of potential disruptions and trade obstacles in the global supply chain. Interestingly, however, various financial markets show a relatively stifled response to proposals for mutual tariff implementation. The calm personality of the response can simply indicate fatigue, and market participants will be decolorized by new announcements. Alternatively, a static sign may indicate that investors are positive and that mutual tariffs are perceived as having a lower impact or that they are likely to be negotiated prior to implementation.

By way of explanation, mutual tariffs are trade obligations imposed by a state to reflect tariffs imposed on exports by other countries. The main purpose is to establish or retaliate a level playing field, allowing the affected country to respond with comparable tariffs if a country collects tariffs on a particular product. For example, if Country A imposes a 20% tariff on steel imports from Country B, it could retaliate by enacting similar tariffs or equivalent goods from Country B.

Currently, some countries are leviing tariffs on US goods and imposes much higher tariffs on goods imported from the US without facing comparable tariffs. For example, India has been identified as maintaining high tariffs on many American products, with an average rate of around 17%, which is significantly higher than the US 3.3% for some Indian products. Similarly, the European Union applies a 10% tariff on US cars. The US has its own tariffs on European cars, but at a much lower rate (2.5%).

The fundamental distinction in economics is to separate from positive analysis (describe the world as it is) and normative analysis (prescribing how it prescribes). Mutual tariffs provide a particularly useful lens for examining this dichotomy. Economic theory generally supports free trade as the optimal state of global commerce, but real-world policy decisions tend to reflect more interventionist approaches. Specifically, the question of whether states should respond to foreign tariffs with their own protectionist measures exemplifies this ongoing debate.

Mutual tariffs indicate a disparity between positive and normative economics. The positive analysis explains that unilateral free trade can generate benefits for consumers and economic efficiency, while also putting pressure on lowering trade barriers by imposing mutual tariffs. However, the normative question is whether states should take principled highlands by avoiding retaliatory tariffs or instead strategically imposed to achieve long-term trade liberalization.

On the one hand, the state may decide that the most economically sound response to tariffs on goods is not to impose retaliatory tariffs of its own. Free trade tends to maximize efficiency by specializing in the production of goods and services with a comparative advantage. In contrast, retaliatory tariffs limit trade, increase consumer costs and distort resource allocation.

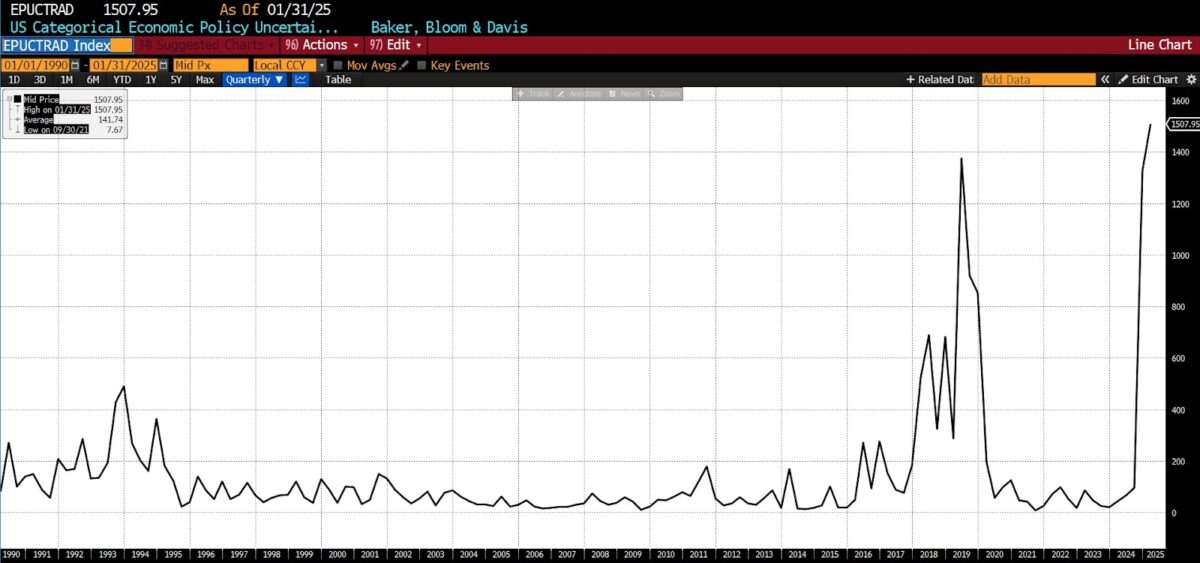

US Trade Policy Uncertainty Index (1990 – Currently)

Even if a country implements tariffs, unilateral free trade remains beneficial. Avoiding anti-enforcement will lower domestic prices and benefit consumers and businesses that rely on imports. Also, not retaliation will prevent damage to trade wars that have historically had economic consequences (considering the Smoot-Hawley tariff law, which exacerbated the Great Repression). Plus, there are moral highlands that are unopposed. Countries dedicated to unilateral free trade can position themselves as a stable open market economy and attract investment and diplomatic goodwill. From this perspective, free trade is the ideal arrangement regardless of how other countries behave.

Another argument is that impose and maintain tariffs could serve as a broader source of freer and productive trade in the long run, and there is another argument that there are mutually customs countries. While imposing tariffs is against the principles of free markets, strategic return and backwards could pressure protectionist states to reduce or eliminate trade barriers, leading to a more open global system. While the practice of imposing mutual tariffs is not without risk, it could force protectionist governments to reassess the costs of obstruction, possibly leading to broader trade liberalization. In that sense, mutual tariffs may be viewed as corrective action, in contrast to the ultimate goal. Proponents of doing so may characterize mutual tariff campaigns (such as those discussed) as practical, free market-oriented interventions, as opposed to dogmatic non-interventionism.

However, even if it is carried out in the spirit of fostering free trade, impose retaliatory tariffs is a dangerous proposition. History shows that such measures can escalate trade disputes, disrupt supply chains, and cause disproportionate harm to domestic consumers and producers. Foreign tariffs interfere with US exports, but could raise domestic barriers accordingly. Moreover, their targeting is inherently political in nature. U.S. prosperity ultimately depends on maintaining open markets and competitive pricing rather than reflecting the protectionism of others. The imposition of mutual tariffs represents a further departure from the general historical principles of the United States that apply unconditional, most favorable nations (MFN) trading policies other than bilateral and regional agreements.

(Two such deviations have recently occurred. Biden revoked his Russian and Belarusian MFN status in 2022, imposing higher tariffs following the Ukrainian invasion, and the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration on Chinese imports in early 2018.)

The debate over mutual tariffs emphasizes the IS/should be central to economic policy analysis. Free trade is the best outcome, and unilateral free trade remains beneficial in the face of foreign tariffs. However, in the government/official field, trade dynamics may be viewed as requiring a strategic response to overseas protectionist policies. However, it ignores the increased costs due to preemptive stockpile, management and compliance changes, and growth uncertainty that slows down the decision to invest and expand, not to mention the tariff threat of any kind (retaliation or other) as a “negotiation tactic.”

Navigating between the science of economics and the practical reality of real-world decision-making is a lasting challenge. The discussion of mutual tariff application identifies broader truths related to all social sciences. Although sound economic theory provides guiding principles, practical applications often need to balance normative ideals with unstable practicalities, especially when political dynamics enter into conflict.

As a scientist, I would prefer a theoretically sound, apolitical (and principled) approach, but the argument presents a valuable opportunity to highlight the contrast between idealism and life force: trade policy, and beyond.