This email suddenly came from a reader in Hillsboro who laughed out loud at my bargain in a recent column for struggling British soccer team Leicester City. I was grateful that someone got it and then I made a double take in his name and replied.

“Are you not the row-headed Mike Connell?”

I don’t know Mike Connell, I’ve never met Mike Connell, but as a child who grew up in Tampa in the 1970s, I piled up in Plymouth to Tampa Stadium on Saturday night to head to Tampa Stadium for former Tampa Bay Lowdies starting defender South Africa.

It is almost impossible to explain how soccer is firmly established in American youth sports and culture. This league, this sport, and these players explain how completely foreign these players were in this sport and how completely foreign these players were when the rowdies first got the field.

In June 1974, owner George Stro Bridge established the Tampa Bay franchise in the North American Football League. He wants to choose the name “rowdies” from the thousands of entries proposed by fans and create a fun and festive environment around the fast game.

The team won their first outdoor game on April 26, 1975, defeating the Rochester Lancers 2-1 after Scottish defender Alex Pringle booted with a corner kick. However, while rowgi was the region’s first professional sports franchise, soccer was still novel here. “Tampa Bay is a soccer and baseball hub,” the local sports columnist wrote two days after Lowdy’s debut victory. “Until six months ago, soccer was Tampa Bay’s best secret since the Manhattan Project,” he cracked, wondering whether American football moguls “have had a serious incident in which they wanted to take football to Tampa Bay.”

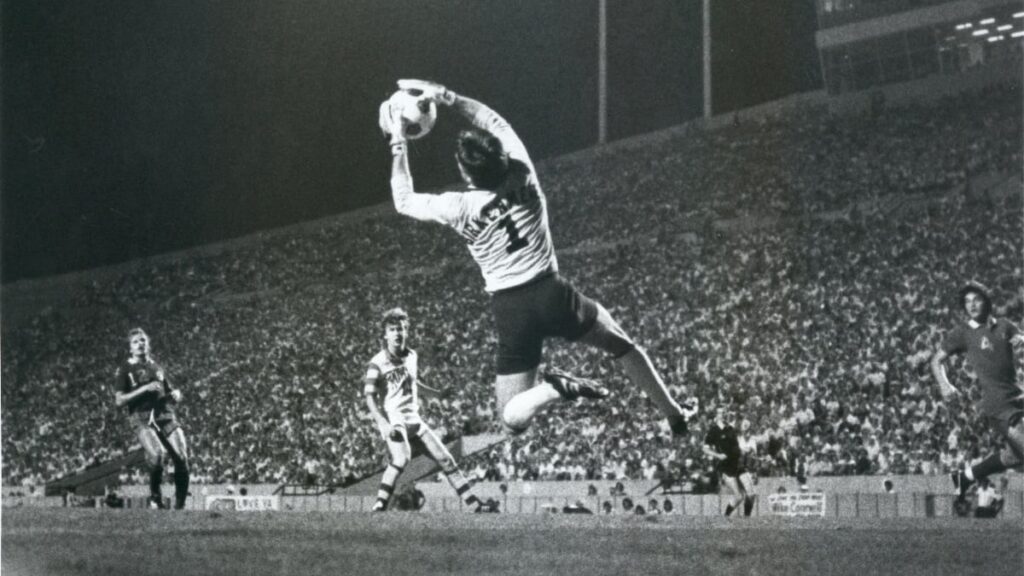

It hurts – but the fair point. Tampa was not the most popular sport breeding ground in the world. The old Sombrero scoreboard game clocks are not like most soccer stadiums around the world, counting down in American style. To save money, Rowdies opened only the west side of the stadium and filled the East Side with fan cardboard cutouts. A golden locked cheerleader called “Krazy George” barked the aisle, pounding the drums. It was a carnival atmosphere by design – colorful, noisy, impulsive and intimate. The fans ate it.

The Rowdies won the game, becoming 16-6 in their first year, beating the Portland Timbers to win their followers to win the 1975 NASL Championship. As Connell explained the other day, coach Eddie Famani had a strategy. We recruit talented players, have them enjoy the game and treat inauguration season as the key to the future of the rowdies.

Spend your days with Hayes

Subscribe to our free Stephenly newsletter

Columnist Stephanie Hayes shares thoughts, feelings and interesting business with you every Monday.

You’re all signed up!

Want more free weekly newsletters in your inbox? Let’s get started.

Check out all options

“He said, ‘We’re introducing the game to areas that we hope will continue,'” Connell (68) recalled. Connell said in that first year Philmani wanted “people and players who want to be accountable and bring moments to their fans.”

It brings me to the second half of the Rowdies story.

The team’s continued success and popularity over time also reflects the contribution of the fuss from the playing field. The club helped to develop sports in Tampa Bay, host camps and clinics, visit schools and build a robust soccer program. It was a difficult climb in the 1970s, but Rowgi overcame skepticism that soccer is a niche sport by showing that everyone who needs to start is the ball and the shoes. And the historically bad start of the Tampa Baybucks in 1976 and 1977 did not hurt the successful row.

The soccer team has also removed barriers between professional players and their fans. They invited the youth team to play at Tampa Stadium before their home game and met fans for postgame drinks and photos at the Bone Shaker in Hyde Park. They sent local players to imagine dozens of appearances each week at almost every event. “We made all these community appearances to support the club and team,” said FalfQuraishi, a defender and member of the 1975 original team who later served as president and general manager of the Lowdies. “People call and say, ‘Can you send players to my kids’ birthday party?’ ”

The players went to high school assembly, facing the ball with seals at SeaWorld, and walked the entire Gasparilla Parade, lifting the soccer ball with their heads, thighs and feet. They appeared in youth games, tournaments, festivals, malls and local restaurants. Once upon a time, my dad called and backup goalkeeper Bob Stettler came to dinner. Stetler then dropped me at the party. One Friday night I was the coolest kid in 7th grade.

That exposure created a connection between players and fans who cut both ways. “It was an honor for me to go out to perform with these players,” said 65-year-old Perry van der Beck, a midfielder of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, who later became executives of the Lowdies. “I’ve never thought about it again. Everyone who played for the noise felt like this.”

“We were their team,” said Van Del Beck, “and they were our team.”

So it wasn’t surprising that many of these early players stayed in Tampa Bay, built their careers and raised their families. Rather than returning to England, Scotland, South Africa or Canada, he became an entrepreneur and diverged into marketing, sports management, education and development. They also continued leadership roles in local soccer clubs and camps, training new generations in old stomping grounds.

“There are a lot of former players who live here,” Quaraishi told me the other day. “We were all very welcoming in this community. The people were very kind. They were very kind. I bump into people who remember how they went to the game.

“To this day, people know that it’s loud. They know well what the name means for the team, the community, the state,” Van Del Beck said. “It’s an honor to have that opportunity.”

Beyond his work promoting youth programs and coaching skills, the former Rowdies founded the Tampa Bay Football Hall of Fame. That first annual banquet in August is scheduled for the team’s 50th anniversary.

“In hindsight, it was a privilege,” Connell said. “I’m very incredibly rewarding. Being a footballer for what the rowgi was doing has become okay. And the acceptance by the community for all of us was so epic and truly home for us. We wore a spell here.”

That might explain why I still have rowdies magnets in my fridge today.